The call came in around 4 p.m., while Adam Abo Sheriah was still at work in his pharmacy in New Jersey. The voice on the other end was sobbing.

It took a few minutes for Adam to understand: His uncle’s home in Gaza City had been hit by Israeli airstrikes. His parents and his brother’s wife and children were inside, taking shelter after their own homes were bombed. Also struck nearby was a block of multifamily buildings in a neighborhood of Gaza City, home to many relatives and their families, who were hunkered down together.

It was the day before Thanksgiving, and Adam’s pharmacy in Paterson was packed with customers, some of them picking up turkeys he was giving away. But Adam couldn’t stay. After the call, he walked out in a daze. His mind swirling with questions, he got in his car and started driving nowhere in particular.

While on the road, he picked up his phone and started calling his family in Gaza. His father didn’t answer. Neither did his mother. He tried his brothers. Nothing. He tried every relative and friend in Gaza.

Over the next eight hours, his frantic calls continued, but few details emerged. Soon it was midnight in New Jersey. The sun was just rising in Gaza. Reports were finally starting to come in. His family’s Gaza home was flattened, the whole block was gone. Voices beneath the rubble cried for help, he was told. But there was no way to dig them out. Eventually, the voices fell silent. Adam’s youngest brother, Ahmed, 37, the ambitious, energetic civil engineer, the children’s favorite who brought toys and fireworks, was found dead in the street.

In the six months since the start of the war in Gaza, Adam and his wife, Ola, have suffered losses on a scale their friends and neighbors in New Jersey can scarcely imagine: In Adam’s family alone, his surviving relatives have told him that 122 immediate and extended family members have been killed in Israeli airstrikes, he said in early April. One of Adam’s cousins has compiled a list, a copy of which Adam keeps with him, of those who are gone. For some, the family has seen or recovered their bodies. Others have been missing so long — with many if not all believed to be buried under rubble — they are presumed dead.

The relatives lost span several generations of Adam’s immense extended family, a range that includes his 83-year-old father, his mother, one of his brothers, as well as aunts, uncles, cousins and second cousins, along with their families and many children. The youngest killed, Adam said, was an 11-month-old granddaughter of one of Adam’s cousin’s.

Ola’s surviving relatives, too, have told her that 70 of her extended family members have been killed since Oct. 7, she said in late March.

Many questions about the killings may never be fully answered. It is unclear why the family’s neighborhood was targeted during Israel’s military campaign in Gaza, and The Times could not independently confirm the majority of family members killed.

The Israeli military, when asked about the strikes, said it could not provide details without being given the coordinates of the attack, which were unavailable. It repeated its overall objective of dismantling Hamas while adding that it “takes feasible precautions to mitigate civilian harm.” The Israeli government has come under sharp criticism from allies for civilian deaths in Gaza.

But to Adam, larger questions about Israel and Hamas, and the politics in Gaza, only deflect from the deeply personal losses he has felt. “I always say, I am not a politician,” he said. “I am just here to tell you about our family suffering, how many people in my family have died, how many of them are still under the rubble.”

Many of Adam and Ola’s surviving family members in Gaza, including Adam’s brothers and their families, Ola’s father, three sisters and a brother are displaced, hungry, injured or battling disease. The luckiest relatives have managed to escape and squeeze into small apartments in Cairo.

“It’s just agony,” Adam said.

Adam, 55, and Ola, 43, Palestinian Americans living in suburban New Jersey, have long known the strain of straddling two worlds. But the war has cleaved their lives completely in two. They follow the daily routine of countless suburban parents: driving their daughters to school, running their business, picking up cat food, doing the dishes, juggling homework and bedtime.

Yet they are always preoccupied with the news from their native Gaza. More than 34,000 Palestinians have been killed since Israel’s bombardment began in October, according to the Gaza Health Ministry, after the Hamas-led attack on Oct. 7 in southern Israel, where assailants killed 1,200 people, according to Israeli officials, and kidnapped around 250 back to Gaza.

Like Palestinian Americans across the United States who are viewing the ever-increasing death tolls with a sense of both helplessness and outrage, Adam and Ola ache for any connection overseas. They stay up deep into the night trying to contact family members in the war zone. Most days, they say they make around 150 phone calls; many go unanswered.

And each day, they grow more frustrated, not just by the suffering in Gaza, but by their adopted country, wondering why the U.S. government remains committed to sending more military aid to Israel, and why it is not doing more for Gaza’s civilians.

Jersey guy

Adam grew up in the Jabaliya refugee camp in northern Gaza with his parents, six brothers and one sister in a tiny home with a metal sheet for a roof. His father, Abdelaziz, a citrus merchant, was displaced as child to the camp after his town became part of Israel in 1948.

The family moved to Gaza City after his father’s citrus business took off. Adam was 11. Like many Palestinians, they built a home compound for their growing and extended family.

Adam stayed in Gaza until he graduated from high school, then in 1984, followed a brother to New Jersey and began what would become a conventional and comfortable American life. He delivered The Star-Ledger to homes in Irvington, N.J., while taking classes in math and science at Essex County College, and pursued a pharmaceutical degree at Fairleigh Dickinson University.

“I’m a Jersey guy,” he said.

Adam and Ola, both American citizens, married in 2010, the same year he opened his pharmacy. The couple and their three daughters, Enjy, 13, Elina, 11, and Taly, 6, live in a white, colonial-style house in Springfield, N.J., a picturesque suburb around 40 minutes from New York City. Adam’s 21-year-old son, Ameer, from a previous marriage lives nearby and works at the pharmacy.

A Monday in March in the middle of Ramadan — the Muslim holy month — illustrated the dual nature of their lives since the start of the war. Adam’s day began as usual, with a round of phone calls to Gaza.

After he tried calling several times, one of his three surviving brothers in Gaza, Hossam, 54, answered. Like Adam, Hossam is a pharmacist. He told Adam that there had been an airstrike near their tent in Rafah the night before.

“This is the kind of answer I always get from them,” Adam said. “‘The bombing is around us, but so far we are OK.’”

While he was on the phone, his three daughters were busy getting their backpacks ready for school.

Afterward, Adam began the first of two school runs, driving his two oldest girls to middle school. They used to walk to school, he said, but after the shooting of the three Palestinian young men in Vermont last fall, he and Ola began taking the time to drive them.

Adam’s car has a Palestinian flag on the dashboard. Along the way, he drove past houses with lawn signs bearing the Israeli flag and reading, “We stand with Israel.” Adam said his day-to-day interactions with neighbors have cooled since the war started.

Back at home, he and Ola tried again to reach relatives in Gaza — brothers, sisters, nephews and nieces. Along with the worry, they carried the burden of knowing they were safe and their loved ones were not.

“It’s hard to enjoy our life,” Ola said, brushing Taly’s hair into a ponytail. Taly is the same age as one niece in Gaza. “We feel guilty,” Ola said.

Ola’s phone rang. It was one of her sisters, Raghda. A car had run over her foot while she was attempting to reach food aid. Ola began crying. Taly automatically ran down the hallway and returned with a tissue for her mother.

Shortly after, Adam received news from Hossam, whose wife had given birth to a baby boy several days earlier. The family is living in tents, and his brother feared that the newborn had contracted hepatitis A.

Adam’s relatives ask him what they should do, but he is reluctant to give advice about where they should go, for fear that the wrong guidance might get them killed.

“Mom, we’re going to be late for school!” Taly exclaimed. Adam and Ola snapped back to their routine and drove Taly to school.

“You drive so fast, bro,” Taly told her father in the car. Adam and Ola laughed. Where had she learned to say “bro?”

“My sisters,” Taly responded.

The survivors

Over the last few months, Adam and Ola said that they have called and emailed the U.S. State Department for help evacuating their remaining family, but as of early April, Adam said that they had only been able to help Ola’s mother, who crossed into Egypt with the assistance of U.S. officials this month.

In total, around 20 of Adam’s relatives, including a brother, his elderly aunt and uncle, and the widow and children of his little brother Ahmed, had made it out of Gaza and into Egypt by the beginning of this month, either through their relation to citizens of other countries or by paying thousands of dollars for private evacuations. Many of them said they were present on the night of the airstrike in November and witnessed the destruction firsthand.

In early March, Adam flew to Cairo for several days to check on them.

Adam’s uncle, Ali Elhassaina, 87, spent most of the time on a bed. His back had been broken in the November airstrike, his face scarred by burns. Adam thought this visit might be the last time he saw him alive.

Before he arrived in Cairo, the news of his family’s death and suffering seemed like a bad dream, he said. Maybe he could wake up from it. But in Cairo, it became real and inescapable.

One cousin, Samira, told Adam about what she experienced the night of Nov. 22. First came one airstrike, she said, then another. The lights went out and rubble began falling on her. “I crawled to my father and mother and patted them. ‘Are you dead? Are you dead?’” From under the rubble, they said no. Her brother managed to pull her and her parents to the surface. But her sister, her sister’s husband and children were gone.

The widow of Adam’s little brother, Ahmed, and three of their children had arrived from Gaza the night before. Adam could barely get his sister-in-law to speak. His 15-year-old niece, Dima, said that when they entered Cairo, all she could think about was a family trip there with her father.

“He bought us anything we asked for,” she said through tears.

‘Helpless’

Adam spent nine days in Cairo. After returning to New Jersey, he drove along the Garden State Parkway on his first day back at work, listening to recitations of the Quran that are traditionally played during Ramadan.

The pharmacy, located in a predominantly Hispanic area of Paterson, was busy.

One of his regulars, Fermina Romero, a native Spanish speaker, spoke enough English to ask him how his father was doing. She had remembered meeting him during the pandemic, when he helped his son at work.

Adam directed her to one of his Spanish-speaking employees, who explained that his parents had been killed. Ms. Romero returned to find Adam and embraced him. “I’m so sorry,” she said. “Thank you,” he replied, then headed to his office in the basement of the store.

Minutes later, he saw on Al Jazeera that the United Nations Security Council had voted for a cease-fire in Gaza, though the United States had abstained.

Adam was disappointed, but not surprised, when U.S. officials later said the cease-fire decision was nonbinding. Palestinians, a relatively tiny minority in America with only around 170,000 people identifying as having Palestinian heritage in the 2020 census, have become accustomed to disappointment in the U.S. government, he said. Adam understands that the position and policy of United States has been to support Israel since its founding, but he wishes that at least conditions would be set on the use of the weapons sent there.

Ameer, Adam’s son, stopped in the office and watched the news with his father. He said he sometimes feels helpless.

“There’s nothing that you can actually do for them,” he said of his relatives. “At the end of the day, you can’t protect them, you can’t save them.”

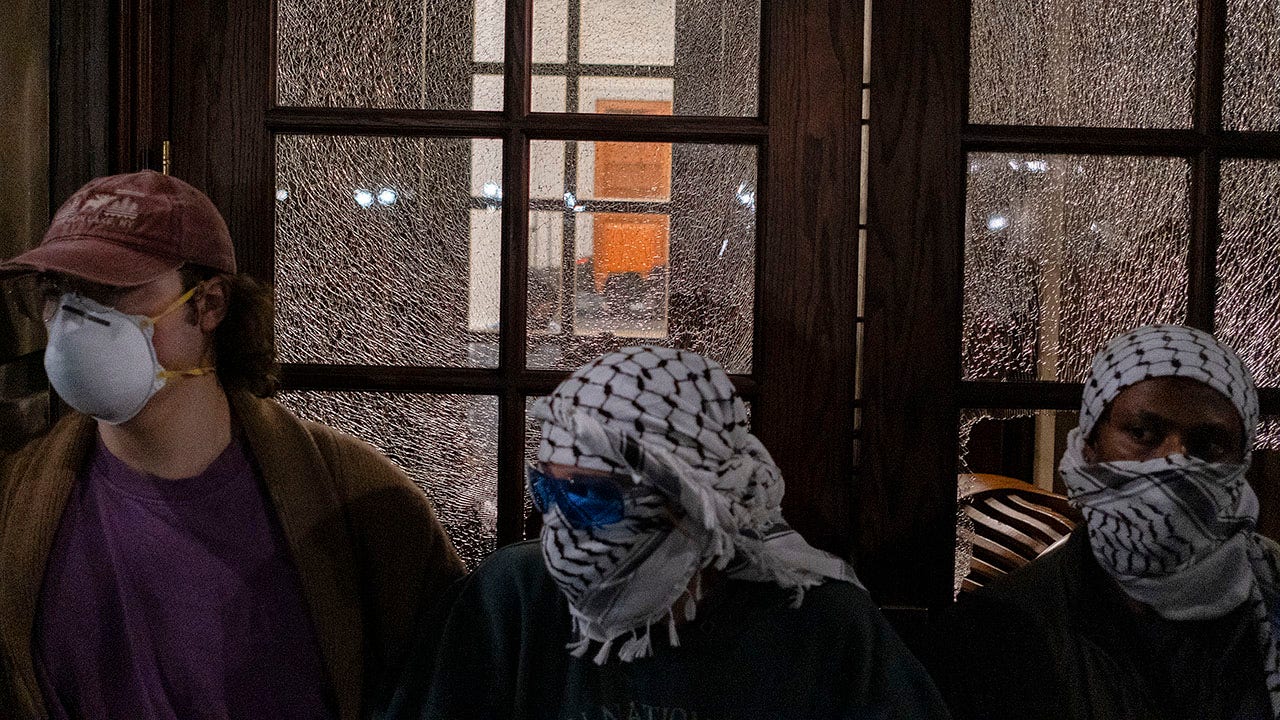

Since the war started, Ameer has joined a few pro-Palestinian rallies. But, he said, he has felt a slight uneasiness, as emotions are high and at times the protests can get “a little bit unruly and don’t necessarily represent the movement properly.”

A couple of weeks earlier, Adam had gone to the United Nations in New York, along with other Palestinian American families, to testify about his family and his experience in front of U.N. leaders, including members of the Security Council and the U.S. Ambassador to the U.N. Adam said he tried to convey a simple message about his dead family members, that “each one of them had a dream and a life.” Sometimes, to make his point at speeches and pro-Palestinian rallies, Adam carries his printed list of the names of his dead relatives that gets longer with every update.

At one point during the U.N. meeting, Adam said, he addressed his comments to the U.S. ambassador, frustrated that the United States has not backed a cease-fire.

“How many Palestinians do you want to kill? Isn’t 1,000 enough? 10,000? 20,000?” he said he asked. “Haven’t you seen enough?”

Giving thanks

Back at home that night, Ola prepared the iftar dinner — the meal after sundown during Ramadan. The kitchen was filled with the fragrance of tomatoes, lemon and olive oil. Handmade meat and cheese pies cooled on a rack. Lentil soup and a stew made from okra simmered.

Ola had reached one of her sisters in central Gaza. Her sister said that bombs were all around them, and that it was hard to find food. “They ask me, when will the war stop?” Ola said. “What do I even tell them?”

Adam thanked Allah for all of the blessings upon them, including the food on their table, “especially when so many people, including our family, don’t have any,” he said.

A little while after the meal, the girls got ready for bed. Adam and Ola began another long night of phone calls. Outside, the neighborhood was dark and peaceful. Inside Adam’s house, the lights were on.

Alain Delaquérière contributed research.