Donald Trump has vowed to appeal his conviction on 34 counts of falsifying business records. Some on the right have argued that the trial was a “target-rich environment” for an appeal. Others have said that the U.S. Supreme Court should “step in” and provide relief to Mr. Trump.

Nevertheless, the process will begin in New York, where state law gives Mr. Trump — and any other individual with a criminal conviction — an absolute right to an appeal before an intermediate appellate court known as the Supreme Court, Appellate Division, First Department.

As a prosecutor and a defense attorney for decades, I have argued hundreds of cases at this court. I’ve looked closely at the Trump case. The burning question now is, could his conviction be reversed on appeal? My answer is, the chances of that are not good.

Mr. Trump’s legal team can approach his appeal on several fronts, but only one, concerning the legal theory behind the falsifying business records charge, is likely to hold out anything more than the slimmest of hopes for the former president.

In recent years, the Appellate Division, First Department, has reversed appeals from criminal convictions in only about 4 to 6 percent of cases. These long odds should come as no surprise. While the Constitution guarantees criminal defendants a fair trial, it does not guarantee them a perfect one.

To warrant reversal of a jury’s verdict on account of an error, the appellate court must find that an error of some kind led directly to the conviction. A technical error that does not rise to that level is called a “harmless error” and will not cause a reversal of a conviction.

In Mr. Trump’s trial, perhaps the best example of harmless error occurred during the prosecutor’s direct examination of Stormy Daniels. The prosecutor elicited intimate details of the sexual encounter Ms. Daniels alleges she had with Mr. Trump and also her testimony that she felt physically threatened by the circumstances of their encounter. Mr. Trump’s defense counsel argued that by discussing the sexual details, which made Mr. Trump appear pathetic, and the statement that she felt intimidated, which made it appear as though the sex was not consensual, the prosecutor had greatly prejudiced Mr. Trump in the eyes of the jury. This was the subject of a mistrial motion, which Justice Juan Merchan denied.

If this supposedly prejudicial testimony is put to the judges on the appellate court, they would ask if the lurid portions of Ms. Daniels’s testimony caused the jury to convict Mr. Trump. The answer here is a clear no.

The defense counsel has cited other issues as grounds for reversal. Take, for example, Justice Merchan’s denial of a change of venue. This is more a political argument that assumes, incorrectly, that because a certain percentage of Manhattan voters did not vote for Mr. Trump, they could not possibly be fair to him. The voir dire process, in which Mr. Trump’s attorneys were fully engaged and ultimately agreed to the jury selected, undermined any claim that a Manhattan jury was incapable of being fair and impartial.

Critics of the case have also suggested that the defense was not made sufficiently aware of the theory behind the charges despite the Sixth Amendment right to notice of the “nature and cause of the accusation.” This is also most likely to fail, because on Feb. 15, Justice Merchan explained in a 30-page decision the precise nature of the charges to be faced at trial.

If the Appellate Division has some concerns with the verdict, it will probably focus on the legal theory that provided the framework for the trial. This will offer the strongest chance for a successful appeal.

That theory was novel and unprecedented. Falsifying business records in the first degree is one of the most common business crimes prosecuted by the Manhattan district attorney’s office. The basic crime is a misdemeanor, but it is elevated to a felony when the false entry in a company’s business records includes “an intent to commit another crime or to aid or conceal the commission thereof.”

When the district attorney brings a case like this, the falsifying business records charge is often charged as a felony, with various underlying common crimes, like state tax fraud, elevating it from a misdemeanor.

Alvin Bragg, the Manhattan district attorney, pursued a theory, and the crime was the violation of New York Election Law 17-152 (conspiracy to promote or prevent election), which makes it a crime to promote someone’s election to public office by “unlawful means.”

In defining “unlawful means” for the jury, Justice Merchan made reference to the tax violations, but also to the Federal Election Campaign Act, which precludes corporate campaign contributions and limits personal ones. The violation of the New York Election Law transformed this rather mundane business crime into an election interference case.

When the appellate court digs into the complicated nature of these charges after Mr. Trump inevitably appeals, it must decide if the charges were unduly vague and thus may have violated constitutional due process.

Since the false filing statute has been broadly construed by the courts, the mere reference to a federal crime would not appear to jeopardize the charges. This will be an uphill climb for Mr. Trump’s lawyers.

Our Constitution makes it difficult to convict criminal defendants by requiring proof beyond a reasonable doubt and a unanimous verdict of all 12 jurors. There is a good reason the prosecution bears such a heavy burden. But once that heavy burden is met and a unanimous jury convicts a criminal defendant, it becomes onerous to overturn the jury’s decision. That is as it should be.

A further appeal to New York’s highest court, the Court of Appeals, is subject to the court’s approval. That choice is informed by the significance of the legal issue presented and the necessity of deciding it for other parties litigating in the courts of New York State. If the Court of Appeals thinks there is a need to clarify the false filing statute in light of the novel theory presented here, this might be a rare instance where it allows a second appeal.

For the case to reach the U.S. Supreme Court, it must reach and get through a decision of the Court of Appeals. But this seems like an unlikely case for the Supreme Court to hear; the appellate issue concerns a New York criminal statute, rather than the type of grave constitutional or federal statutory issue ordinarily reviewed by the Supreme Court. Yes, an “unlawful means” behind the violation of state election law referred to the Federal Election Campaign Act, but there is no federal issue directly implicated by this state prosecution.

By all indications Mr. Trump received a fair trial by a jury of his peers presided over by a very able jurist. He faces long odds against winning on appeal.

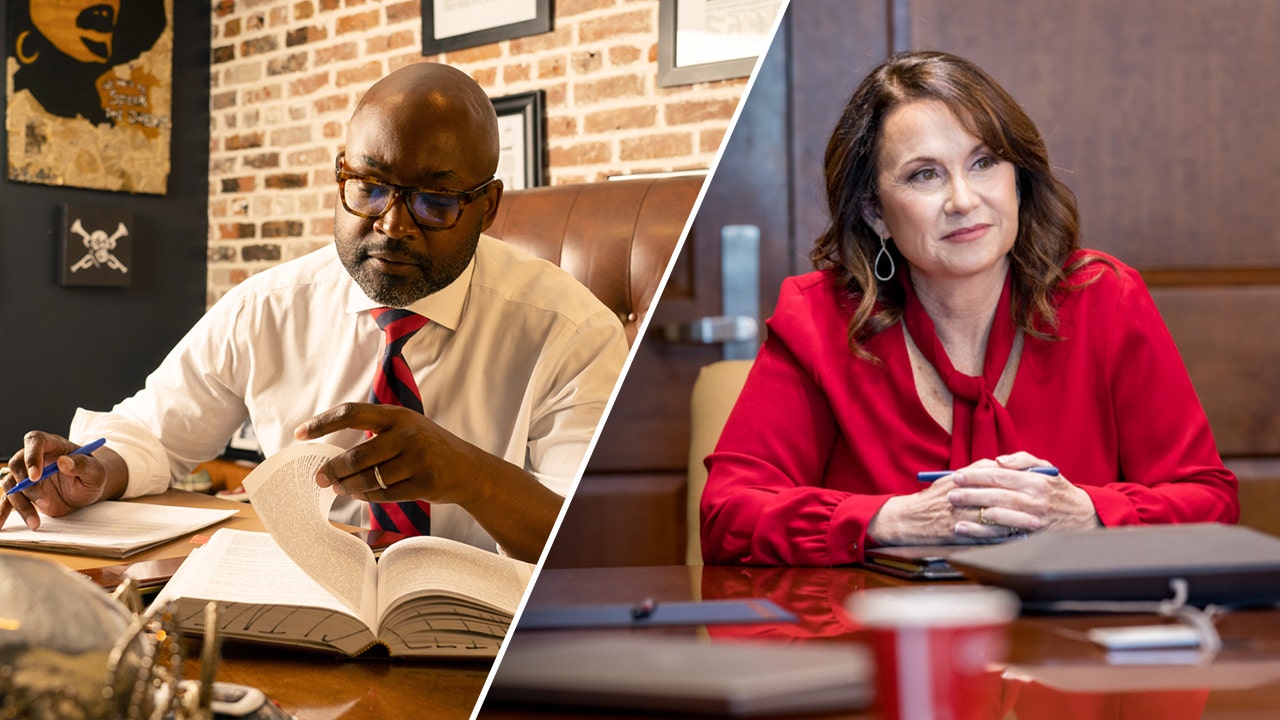

Roger L. Stavis, a former prosecutor, is a defense and appellate lawyer and a co-chair of the white collar defense and investigations practice at Mintz & Gold in New York City.

The Times is committed to publishing a diversity of letters to the editor. We’d like to hear what you think about this or any of our articles. Here are some tips. And here’s our email: letters@nytimes.com.

Follow the New York Times Opinion section on Facebook, Instagram, TikTok, WhatsApp, X and Threads.