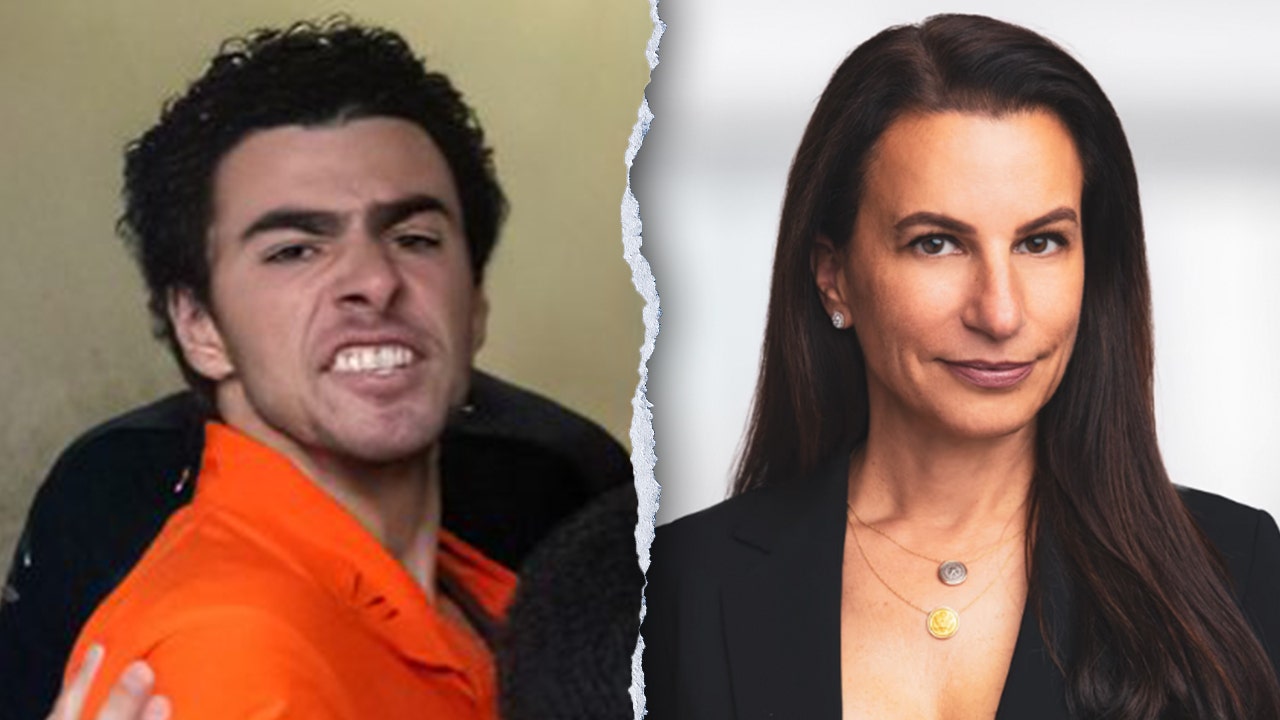

On June 10 of last year, Ted Kaczynski, the homegrown terrorist known as the Unabomber, was found dead in his cell in Butner, N.C. Mr. Kaczynski, who had spent 25 years in federal prison for murdering three people and injuring 23 others with mail bombs, had reportedly died by suicide.

The news jarred me. I was writing a novel about Mr. Kaczynski.

One year later, the book is finished and the news has faded, but I’m still untangling the mythologies that surrounded the Unabomber’s life — of the tortured outcast who sought refuge in the American West — from the ones that influenced my own.

I grew up in Missoula, about 80 miles from the Unabomber’s shack in the Montana wilderness and was 11 at the time of his capture. What I remember most from those days is a sense of disturbance. I saw helicopters in the sky and heard the hushed anxiety in my parents’ voices. I didn’t know who the Unabomber was or what he had done, but I could tell it was important — and dark. So much so that my home state was suddenly the center of national attention.

Until then I’d felt about as far from the center as a kid could be. Western Montana in the 1990s was not a place that made the national news, save for an occasional environmental disaster and the annual Testicle Festival — a days-long debauch of fried steer genitals that attracted seedier press. To me, home meant the patchy fields behind the hospital where my soccer team practiced in the spring, the green rattletrap chairlift at the three-run ski hill the school bus brought us to every Friday afternoon, the dismal mall my friends and I wandered in endless loops.

At first I was confused about who the Unabomber actually was. Was he an environmental avenger striking back at timber companies, or a madman blowing up computer rental stores? People seemed to think he was smart. He’d gone to Harvard. I knew what that was. Then I saw his shack. Why would a smart person live that way? And why here?

The sudden media attention hinted at the answers. I heard the words “cabin,” “remote” and “wilderness” repeated on the evening news with an increasingly romantic luster. I began to see how people on the coasts viewed my home state: as a wilderness of possibility. A refuge for ruffians, seekers, dropouts, dreamers and the occasional psychopath. Someplace you could go if things didn’t work out. T-shirts and coffee mugs bearing the slogan “The Last Best Place to Hide” popped up in local souvenir stores.

My life in Montana wasn’t romantic. It was distinctly suburban. I lived two blocks from the local high school. We shopped at Kmart, rented movies at Blockbuster and ate at a fast-food pan-Asian place called the Mustard Seed. I listened to Nirvana and wore clothing emblazoned with Michael Jordan. I had never been hunting, and I had fished exactly once. Newspaper headlines first alerted me that I lived on the frontier. And I wondered what this meant.

Thinkers like Emerson and Thoreau made the idea of the wilderness aspirational, as a place to purify one’s spirit and find one’s true self. Our heroes and outlaws have often played out their destinies there, from Lewis and Clark to Billy the Kid to Kerouac and Cassidy. But the West is a place like any other place. We just use it as a mirror for the dark, untamed aspects of our national character.

Mr. Kaczynski’s story followed this blueprint. He left behind a successful career in academia to test himself in nature. Once there, he became an avatar for a much older myth — of the monster lurking in the woods, terrorizing a complacent society. His postal delivery bombs were a warped modern twist.

Absorbing his story over time, I began to wonder if my purpose lay elsewhere. If Montana was a playground for malcontents with pioneer fantasies, I’d get out, become a screenwriter in Los Angeles, washed clean of my youth..

Mr. Kaczynski’s capture was my first encounter with the poison pit at the center of the American dream. I suddenly felt like a stranger in the only place I’d ever really known.

We are all homeless here. Our manic national ambition makes every horizon a proving ground. To stay in one place doing one thing is to fail.

Propelled by our ambition to remake ourselves, we careen past one another, oblivious to the fact that we’re following a pattern as old as our country.

So it was with Mr. Kaczynski. Homeless and lashing out, confused, pedantic, reactionary, he pretended to have new ideas to mask his old ambitions, cherry-picking from French philosophers, Luddites and environmentalists. But the truth is, he was just trying to justify what he and so many other boys here want — to get away from their parents, transcend their peers and remake society in their own image.

The media got him wrong. In seeking to romanticize Mr. Kaczynski, reporters gave him Thoreau-like qualities — framing him as a philosopher who found purpose in the woods, dark as it was. But his only innovation was a new, cowardly kind of violence. Mr. Kaczynski never really saw Montana, the wilderness or the West itself, as it truly was. For him, its main attribute was its lack of people. He was a twisted embodiment of the dream of the frontier that was poisoned from its inception.

Strangely, Mr. Kaczynski’s mythology seems only to have grown since his death. Young people still spread messages from his manifesto across social media, creating their own story of “Uncle Ted” as a fiery anti-technology prophet. We must hate ourselves, I thought, reading their posts, for the way we seek heroes from the worst among us.

We are all fed myths about our homes, whether it’s Montana as the last best place to hide or New York City as the cultural capital of the world. But these are just stories, often relying on outliers like Mr. Kaczynski. Our hometowns are far more complex than these mythologies, but seeing them as they really are — and loving them in all their tragic beauty — leads us away from destruction and isolation, to community and stewardship, a form of deeper purpose.

I spent my late teens and twenties on the move, anxious and driven and confused. I thought I was searching for purpose and home, but I was rebelling against the very idea. Like a good American boy, I was chasing the American dream: not a house and a two-car garage, but rebellion itself.

Last year, weary from the lonely and grief-stricken years of the pandemic, I moved back to Missoula and began life anew. The three-run ski hill is gone and the town has spread to fill the valley, but there are still towering mountains and looming trees and plenty of places to get lost.

Each day I wake up and try to see Montana for what it is. Golden grass on the dry hills, a big sky that generally runs from gray to darker gray, clear-cuts and abandoned mines and meth-ridden towns and glittering stands of wilderness so stunning they bring me to tears. It’s complicated and beautiful and older than I can possibly imagine. One day, in the marrow of my bones, I hope to know it only as home.