There are more heavily trafficked routes across the Baltimore Harbor than the Francis Scott Key Bridge. The Harbor Tunnel carries double the daily traffic of the Key Bridge and the Fort McHenry Tunnel much more than that.

But the Key, with its gently sloping arch and views that no tunnel could match, had become an emblem of Baltimore’s identity as a working port city.

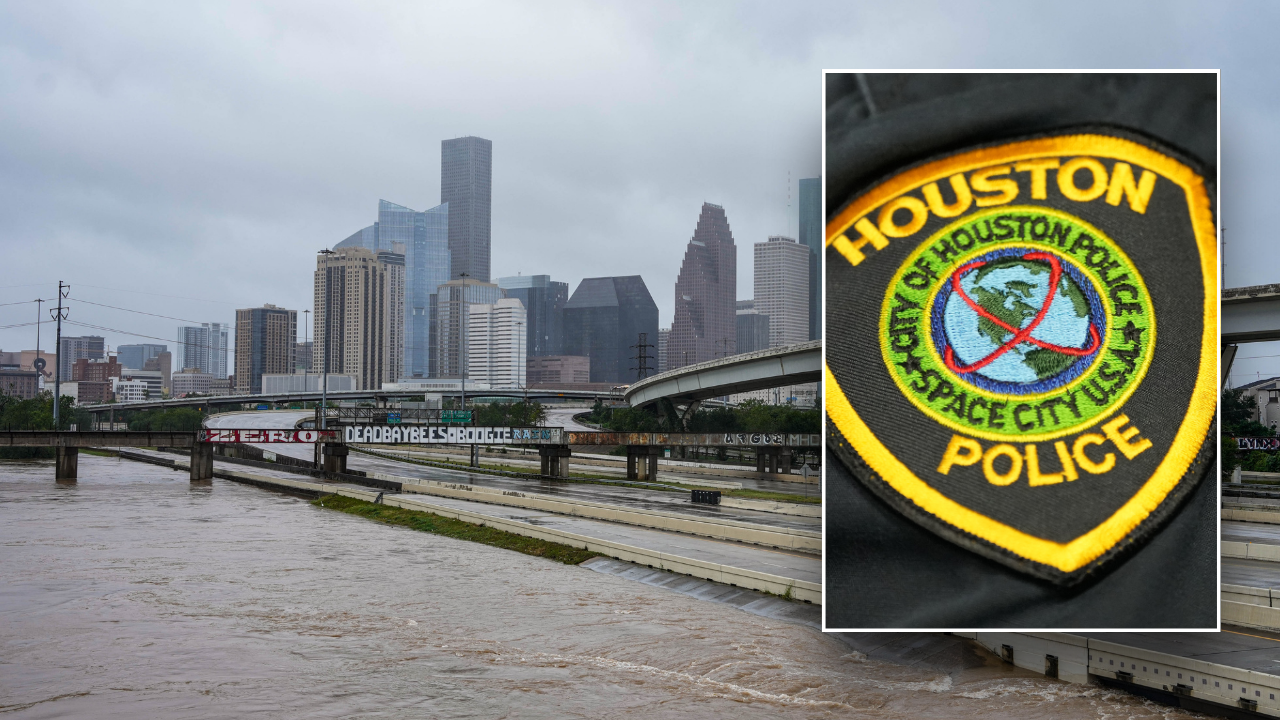

On Tuesday, from vantage points across the harbor, people stood in disbelief at the sight of parts of the 1.6-mile span jutting jaggedly out of the water, the result of a catastrophic cargo ship crash that toppled the bridge and left six workers missing.

“It’s the blue-collar bridge,” said Kurt L. Schmoke, Baltimore’s mayor in the 1990s and now president of University of Baltimore. The Chesapeake Bay Bridge, 22 miles away, the only bridge in Maryland that was longer, is all about leisure, a gateway to the beach. The tunnels are all function, a way of all but bypassing Baltimore on the way from Washington, D.C., to New York City.

“The Key Bridge,” Mr. Schmoke said, “was definitely for work.”

When the Key Bridge opened in 1977, the Harbor Tunnel was constantly clogged with traffic, reflecting the increased commuting among the fast-growing suburbs of Baltimore and along the I-95 corridor. The bridge was a release valve for the traffic and a godsend for the working-class communities that sat on either end of it. They now had a direct route to the jobs at the plants and distribution centers that line the Harbor.

“The bridge spanned working Baltimore, both metaphorically and literally,” said Rafael Alvarez, 65, the son of a harbor tugboat engineer who has written more than a dozen books about Baltimore’s working class.

On the northern end was Sparrows Point, once home to the massive Bethlehem Steel Plant, which was once the largest working mill in the world and is now the site of distribution centers for Amazon, Home Depot and Under Armour. On the other end, Curtis Bay, long home to chemical plants, including a paint company that Mr. Alvarez remembers emitting white clouds so thick they had to close the bridge.

Tens of thousands of Baltimoreans lived and worked in these areas, Mr. Alvarez said.

The six men who are missing were part of this tradition of working Baltimore: members of a construction crew, working overnight hours filling potholes on the bridge.

As the morning unfolded, and cars and trucks from a legion of government agencies went to and from the collapse site, some of the people who knew the bridge best were forced, this time, to take it in at a distance.

They gathered on a highway embankment across from a Dollar General to get a look at the broken bridge. There were whispered conspiracy theories among the crowd, pointed concerns about getting to work and doctor’s appointments and bafflement at how this could have happened.

Others just recollected.

“When I got my license in ’75, the only way to get back and forth was the tunnel,” said James Metzger, 66, retired from the automotive industry.

From the windows at his high school, not far from where he was standing, Mr. Metzger would look out and watch the bridge being built, he said. Around that time he was seeing a girl who lived on the other side; a bridge had romantic implications along with everything else.

One day in 1977, Mr. Metzger said, his father, a truck driver, was coming back home from his route and happened upon the bridge’s ribbon cutting. His father had seen the governor, he said, and even kept a piece of the ribbon. The bridge had been a part of their lives ever since.

Until Tuesday morning, when Mr. Metzger’s current girlfriend had called. “She was on the way to work,” he said. “She said, ‘I’m seeing police cars and helicopters. And the Key Bridge is gone.’”