New data from Texas shows a possible consequence of abortion bans: a rise in infant mortality.

In 2022, the year after the state’s six-week abortion ban took effect, deaths of infants before their first birthdays increased 13 percent, an analysis published Monday in JAMA Pediatrics showed.

The increase was driven by congenital defects or chromosomal abnormalities, it found. The number of babies with such conditions who died rose 23 percent in that period, compared with a 3 percent decrease in the rest of the country.

Fatal fetal anomalies include trisomy 18 or conditions in which fetuses are missing kidneys or parts of the brain. Many are not discovered until the anatomy ultrasound at roughly 20 weeks of pregnancy, well after the gestational age limit in Texas’ abortion ban.

The results “suggest that additional live births occurring in Texas in 2022 disproportionately included pregnancies at increased risk of infant mortality, particularly those involving congenital anomalies,” the study’s authors wrote.

The period of the study did not include most babies born after Dobbs, the Supreme Court decision in June 2022 that ended the constitutional right to abortion. Seventeen states now have total bans or six-week bans, and most do not have exceptions for fatal fetal anomalies.

It takes a long time for complete data on births and deaths to be released, so it is too early to know much about the effect of these bans on infant mortality. But the new study adds to research on earlier bans showing a link to increases in infant deaths, births with chromosomal abnormalities, and maternal health complications.

The new analysis “is a provocative finding that should be taken seriously,” said Charles Stoeker, a health economist at Tulane and an author of another study linking abortion restrictions and infant deaths. “It’s not fully convincing alone, but there is an emerging body of evidence that show that these abortion restrictions have serious negative consequences for infant mortality.”

Women who end their pregnancies because of maternal or fetal health complications have become a focus of the abortion debate.

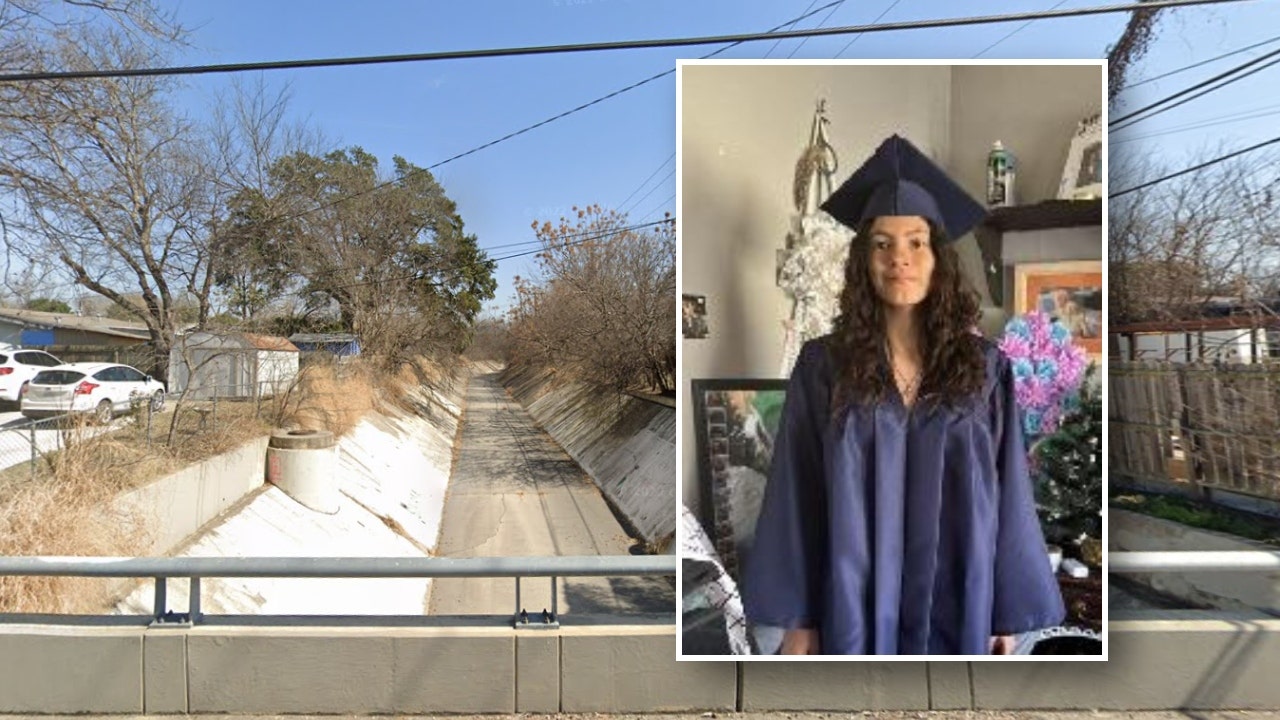

In a case that drew national attention last year, a Texas woman, Kate Cox, had her fetus diagnosed with a fatal chromosomal abnormality, and she traveled out of state for an abortion after the Texas Supreme Court stopped her from having the procedure. The U.S. Supreme Court is set to rule soon on an Idaho case about whether doctors in states with abortion bans can provide emergency abortions to women in dire medical condition.

Abortion opponents say that fetuses, regardless of a fatal diagnosis, “deserve every chance at life,” said Amy O’Donnell, the communications director for Texas Alliance for Life.

“It is heart-wrenching for any parent to lose a child, and our sympathies go out to families who have experienced such loss,” she said. “Nevertheless, no disease, disability or disorder justifies abortion.”

In 2022, the year of focus for the study, infant mortality increased nationwide by 2 percent, after decreases since 1995. Researchers are not sure why, but they say the pandemic may have played a role — because of infection, stress or fewer doctor visits. Also, the United States has had declining maternity care in some places, especially for complicated pregnancies.

But in Texas, the number of infants who died increased significantly more — 2,240 infants died, 255 more than in 2021, an increase of 13 percent.

About one-fifth of infant deaths in the United States are because of congenital defects. In Texas in 2022, one-fourth were, the researchers found, using federal death certificate data.

Data shows that most women with fatal diagnoses choose to terminate their pregnancies.

“As a doctor, these moments are both haunting and heartbreaking,” said Dr. Maria Isabel Rodriguez, an obstetrician and gynecologist at Oregon Health and Science University who researches reproductive health policy. “In a post-Roe America, options depend on where a person lives and what their resources are.”

The authors of the new study hypothesized that other factors might have contributed to the rise in infant deaths in Texas, such as financial or emotional stress among women with unintended pregnancies.

Infant deaths because of maternal pregnancy complications increased 18 percent in Texas, compared with 8 percent in the rest of the United States. The study did not have detail on these complications, but in general, maternal health issues are a main cause of fetal or infant mortality. Although state abortion bans have exceptions for the life of the mother, they do not necessarily have health exceptions, an issue before the Supreme Court now.

The data did not include women’s income or race. Overall, Black babies have a higher infant mortality rate than among other large groups.

As more data becomes available, the ramifications of abortion bans will become clearer, said Suzanne Bell, an author of the study and an assistant professor at Johns Hopkins: “We’re starting to see more evidence of the downstream effects of those policies.”

Josh Katz contributed reporting.