In the last decade, it has proved surprisingly hard to put politicians accused of corruption behind bars. Appeals courts have reversed several convictions. And juries have occasionally thought the officeholders’ behavior didn’t meet the high standard for corruption.

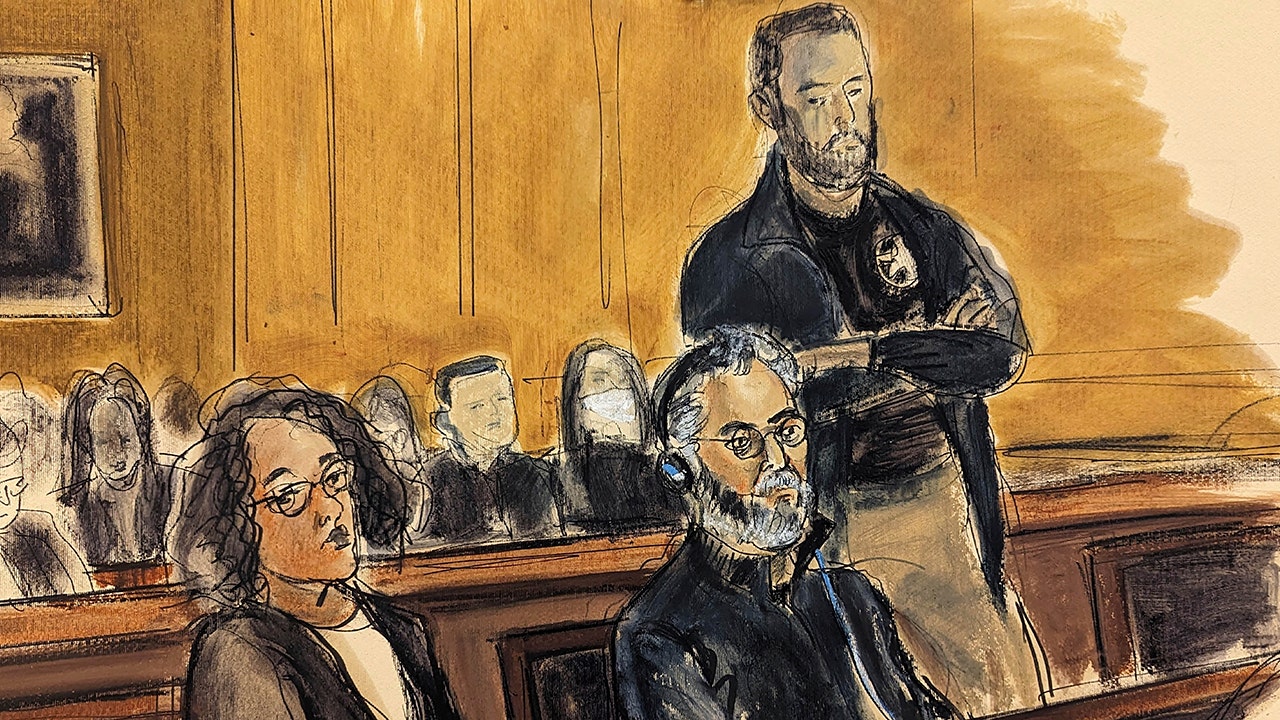

Senator Bob Menendez of New Jersey, who was arraigned yesterday in a federal bribery case, is both an example of the conundrum and a test of whether federal prosecutors now know how to overcome it. In the senator’s last corruption trial, in 2017, jurors couldn’t make sense of the gifts and favors he’d received from a wealthy eye doctor. Were they illegal — or just the sort of thing friends do for each other?

Menendez, a Democrat, faces new charges for taking cash, gold bars and a Mercedes-Benz convertible. In exchange, prosecutors say, he attempted to disrupt criminal cases and used his position on the Senate Foreign Relations Committee inappropriately. He introduced a businessman who sought funding to a member of Qatar’s royal family, and he helped push through aid and weapons sales for Egypt, the charges say.

This time, prosecutors are hoping to make the indictment stick. In today’s newsletter, I’ll explain why the bar for conviction is so high — and what government lawyers need to do to succeed, including against Menendez, where previous cases have failed.

A tough standard

The Supreme Court is the main reason for the Justice Department’s difficulties. In a 2016 decision, the justices threw out a graft conviction against Bob McDonnell, a former Virginia governor. McDonnell, a Republican, used his office to help a businessman who’d lent him $135,000 and gifted luxury items and vacations.

But the justices didn’t think that was proof of corruption. They said it wasn’t enough for public servants to provide political courtesies, like setting up a meeting for a friend. The politicians needed to have a specific quid pro quo involving an official act or a governmental decision. The ruling effectively narrowed the legal definition of corruption.

The McDonnell case had an immediate impact. The following year, a federal appeals court in New York tossed out the convictions of two top state officials: Sheldon Silver, former Democratic speaker of the State Assembly, and Dean Skelos, a Republican who once ran the State Senate. These reversals — and there were others — were based on the Supreme Court’s new standard. The appeals court said that the jurors had found the defendants guilty without being told about the new requirement of a clear quid pro quo.

Adapting

But prosecutors quickly learned their lesson. At retrials, they convicted both Silver and Skelos using much of the same evidence. And they fixed the problem that hurt them initially: They focused on the specific exchange of services for payments and made sure the juries understood the new definition imposed by the McDonnell ruling.

The case against Menendez is a different kind of test. It relies on new charges, not the same facts from his 2017 mistrial.

The new charges detail the relationship between Menendez, his wife and three New Jersey businessmen. The evidence, prosecutors say, shows that the senator and his wife (both of whom pleaded not guilty) took money, gold and the car in exchange for their influence. Then the couple tried to cover up one of the bribes by making it look like a loan. The trick for prosecutors this time is making sure the Menendez charges fall on the right side of the narrow line that the Supreme Court drew in the McDonnell case.

While that has sometimes proved difficult in the past, it’s not impossible. Last week, the same appeals court that reversed the convictions against Silver and Skelos reinstated bribery charges against a different New York politician, Brian Benjamin, the former Democratic lieutenant governor. The key difference was that the prosecutors had shown enough evidence of “an explicit quid pro quo” for the case to be revived, the appellate judges ruled. Prosecutors say that in exchange for campaign contributions, Benjamin steered $50,000 in state money to a developer.

If the jurors in the coming Menendez trial see the same thing, the charges against him may stick this time.

THE LATEST NEWS

Biden’s Budget

TikTok

-

House Republicans plan to vote this week on a bipartisan bill to force the Chinese owners of TikTok to sell the company. (Here’s why many governments oppose the app.)

-

Trump no longer supports banning TikTok. When asked why, he said that doing so would make young people “go crazy” and would help Facebook, which he called “an enemy of the people.”

Media

-

Deadspin, a sports news website, was sold to a European digital media company.

-

In a bleak media landscape, start-ups like Puck and Semafor have found some success.

Other Big Stories

Opinions

The princess’s photograph scandal is a piece of careless fakery that makes the British royal family look amateurish, Lindsay Crouse writes.

Museum-worthy posters: You’ve likely seen a movie poster by the designer Dawn Baillie. She came up with the “Silence of the Lambs” poster and captured the dystopia of “The Truman Show.” Baillie’s work is the subject of a new exhibition at Poster House in Manhattan.

“A poster’s job is to celebrate a film in one frame,” she told The Times. “The job is well done when an audience is piqued and the poster makes it to the dorm room wall.” Read an interview about her process and see some of her most famous posters.