Throughout a series of congressional hearings about what public schools and universities are doing to combat antisemitism, Republicans keep hammering school leaders on one question.

Why haven’t they fired educators accused of antisemitism?

The accusations have come during a wave of demonstrations and discussions about the Israel-Hamas war on the campuses of public schools and universities. The Republicans leading the hearings have argued that school administrators have not done enough to discipline employees whose behavior they say has crossed from protected free speech into antisemitic hate speech and harassment.

But even defining what sorts of activities and speech are antisemitic is also hotly debated, including among Jewish families and organizations.

School leaders have had a variety of responses. Some have promised to crack down on individuals, by name, while others have refused to provide any information about employee discipline.

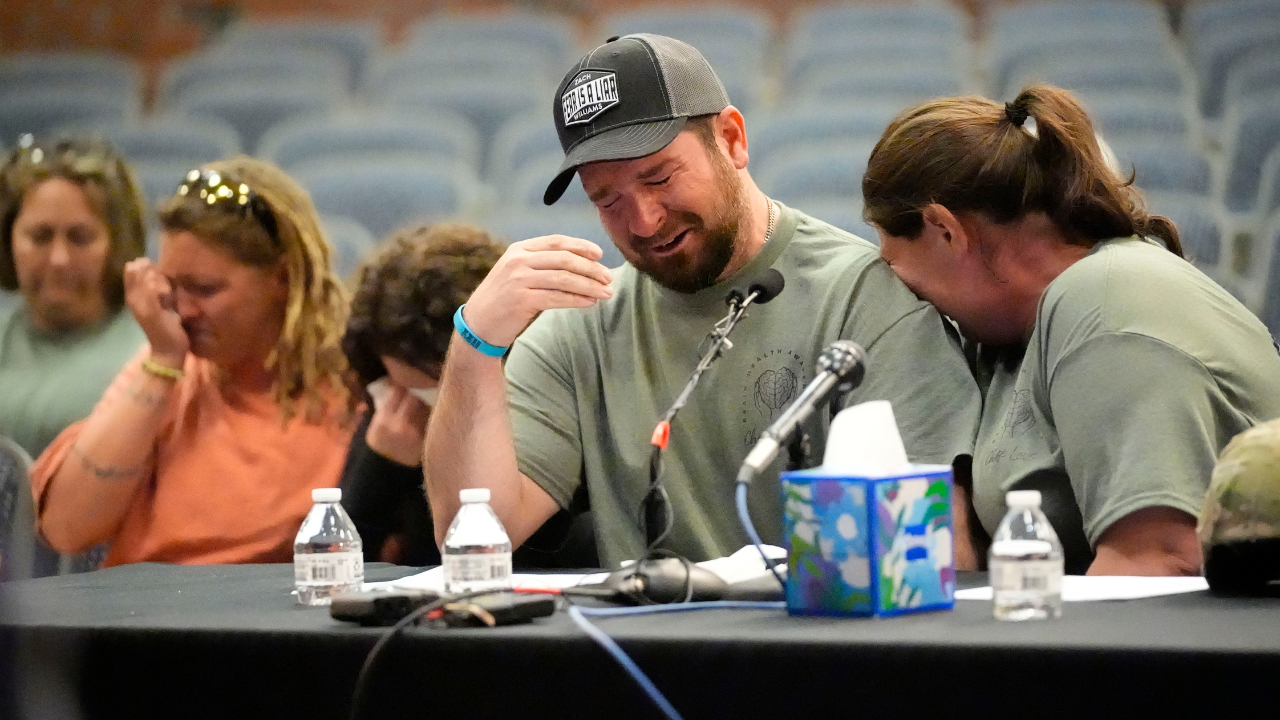

At one of the hearings at the Capitol this month, the New York City schools chief repeatedly leaned on one legal phrase: due process.

“We do not have the authority — just because I disagree — to just terminate someone,” the chancellor, David C. Banks, said. “That’s not the way it works in our school system.”

The different approaches by public school and college administrators, both to congressional questioning and to the discipline itself, are a reflection of how discipline has become one of the thorniest challenges for schools trying to navigate tensions over the Israel-Hamas war.

As complaints rack up over teachers who promote protests or professors who spar with students online, leaders have been thrust into a deeply charged issue touching on a complex web of concerns. Among them are gray areas of free speech rules, employees’ union rights and heated debates over contested phrases like “from the river to the sea.”

To some Jewish students and parents, administrators are not doing enough to reprimand or even get rid of employees who they say are allowing hostile views toward Jews to fester in classrooms and lecture halls. Yet to some Arab and Muslim families, many leaders have gone too far, infringing on educators’ rights and unevenly enforcing the rules about what warrants discipline.

The tension over discipline is likely to re-emerge on the national stage later this month, when the presidents of three more universities, Rutgers, Northwestern and the University of California, Los Angeles, become the next to testify in Washington.

At a hearing last month, Columbia University’s president, Nemat Shafik, divulged that two professors — whom she identified by name — were under investigation for making “discriminatory remarks.” One of them, who described the Hamas-led attack on Israel as a “resistance offensive” in an article, would never work at the school again, she said.

Nine days later, the university’s senate accused the administration of having breached professors’ due process rights and their privacy.

“These actions show little respect for clearly established protocols,” read a resolution approved by the senate.

The Columbia leader’s approach before Congress stood in stark contrast to the testimony of public school leaders at a separate hearing. The Berkeley Unified School District superintendent, Enikia Ford Morthel, repeatedly declined to share even broad details of punitive measures taken against district employees, noting that California has strict confidentiality rules that govern personnel details.

The contrasting playbooks were in part a reflection of the chasm between the legal and professional standards for public school districts and higher education institutions. While most professors are granted broad rights to academic freedom, schoolteachers are far more constrained in their choice of lessons, as well as in their speech as public employees.

Some episodes have centered on clearer cases of explicit hate speech or antisemitic tropes. But many revolve around more nuanced situations, such as how teachers have discussed the war in history and social studies courses, or how their political behavior — such as helping to organize a walkout to call for a cease-fire in Gaza — may influence students’ views.

In Berkeley, for example, the Brandeis Center, a Jewish civil rights group, filed a complaint earlier this year, arguing in part that the district had “refused” to discipline teachers, including some who framed the Hamas attack as “resistance” or called Israel an “apartheid state” in their classrooms.

Rachel Lerman, the center’s vice chair and general counsel, said that many Jewish families feel like if another group were to face similar targeting in schools, “we would see results.”

“It’s not about silencing speech,” Ms. Lerman said. “It’s about what’s appropriate in the classroom under the school’s own rules and California’s own laws.”

A confrontation over similar issues unfolded this week when Republicans questioned Mr. Banks, New York City’s schools chief, over why he had reassigned, but not fired, the principal of a high school where students raucously protested a Jewish educator who posted support for Israel on social media.

Mr. Banks repeated that every school employee is entitled to due process. In a strong union town like New York, most teachers and principals are entitled to hearings where they can respond to accusations of misconduct before officials impose discipline, including firing them.

On an issue as sensitive as the Israel-Hamas war, it may be no surprise that some families “may not ever feel the sanction was appropriate,” said Cheryl Logan, a former superintendent in Omaha and expert in educational leadership.

District leaders, though, must strike a delicate balance. “People have private lives,” she said, “and they work in public schools.”

Some states like Massachusetts broadly restrict all public employees from political behavior during work time. A teacher would not be allowed to print pamphlets for a pro-Palestinian demonstration on a school computer, for example, or seek to advance pro-Israel views during class time.

Still, experts said the rules can be murkier for a teacher’s speech online or out of school hours. Many districts have also previously given educators leeway to show support for certain political or social causes, like Black Lives Matter or Ukraine in its war with Russia.

Those issues of what’s permitted merged in a recent dispute in Montgomery County, Md., where the district was sued after it suspended three teachers who used contested language to describe the war in Gaza.

One of the teachers often wore “Free Palestine” buttons to school, and was put on leave after a staff member complained that she had put the contested phrase “From the river to the sea, Palestine will be free” in the signature of her internal emails to colleagues, according to the suit. Some Jews see the phrase as antisemitic. The teacher viewed it as an “aspirational call to freedom and dignity for the Palestinian people,” the suit said.

Zainab Chaudry, the Maryland director for the Council on American-Islamic Relations, said she worries of a “clear double standard,” in which teachers who support the Palestinian cause do not receive the same due process rights as those who back Israel.

“We’ve never seen this level of suppression of free speech,” she said, adding that one major challenge “is that there are no clear-cut guidelines in terms of what’s acceptable and what’s not.”

In New York City, Mr. Banks told a congressional subcommittee on education this week that the phrase “from the river to the sea” was not allowed in schools. The New York Civil Liberties Union later said that many educators were unaware of the rule and that it believed a strict ban would most likely be unconstitutional.

As the chancellor testified in Washington, a group of pro-Palestinian teachers held a demonstration on the steps of the city’s Education Department headquarters. Among them was Pam Sporn, a retired teacher in the Bronx who said her mission as an educator was to expose her students to the world.

Ms. Sporn said she often dug “into controversial historical and current issues” in her classroom, and was fortunate to work in schools “where we had that freedom.”

Today, though, she said, “I would be in so much trouble.”

Olivia Bensimon contributed reporting.