President Biden delivered an energetic and impassioned speech that was as much a campaign kickoff as it was a State of the Union, leveraging what is expected to be one of his largest audiences of the year to make a forceful case that he was fit enough for another four years.

Mr. Biden has rarely been called a bold orator. But he arrived on Capitol Hill on Thursday with the benefit of mercifully low expectations after unrelenting Republican attacks on his mental and physical fitness.

This was not a typical State of the Union. The speeches are often a laundry list of accomplishments and an equally long set of promises. Instead, this was Mr. Biden framing the year, just as his White House and Wilmington-based advisers want, as a stark choice between two candidates.

He opened with Donald Trump. He closed with Mr. Trump. And in between he taunted and teased the Republican lawmakers in the chamber who were protesting and jeering, readily taking the bait — and even one person’s pin — to score political points of his own.

Here are four takeaways from Mr. Biden’s fiery election-year State of the Union:

A feisty speech aimed at combating the notion that Biden is too old.

Mr. Biden came into Thursday’s speech determined to use the high-profile moment to beat back accusations that he is too old for a second term.

He delivered feisty remarks at a near-shout in an effort to show energy and vitality. He sparred with Republicans in the chamber several times, diverting from his prepared remarks to ad-lib his retorts. And as he neared the end of his speech, the president joked about his age.

“I know I may not look like it, but I’ve been around a while,” the 81-year-old commander in chief said to chuckles in the chamber. “And when you get to my age, certain things become clearer than ever.”

If his primary mission was to avoid a gaffe that would feed into concerns about his age, as expressed by broad majorities in both parties in multiple polls, he succeeded in that mission. But despite a performance that was more spirited than he often delivers, it was unlikely to quell the concerns, especially from Republicans, who have made questioning Mr. Biden’s competency a centerpiece of their 2024 strategy.

The morning of the State of Union began with an ad from Mr. Trump’s super PAC questioning if Mr. Biden would live to 2029. By evening, Donald Trump Jr. said on social media that Mr. Biden looked “like a reanimated corpse.”

Biden leaned repeatedly on one phrase in particular — ‘my predecessor.’

Mr. Biden may not have mentioned Mr. Trump by name, but he left little doubt about whom he was speaking — and whom he was running against.

The president outlined sharply divergent views of America — its government and its role in the world — with “my predecessor,” a phrase he first used fewer than five minutes into the speech.

He talked about how “my predecessor” had tried to rewrite the history of the Capitol riot on Jan. 6, 2021, how “my predecessor” had failed to care as the pandemic began to rage across the nation almost exactly four years ago, how “my predecessor” had done little to combat China and how “my predecessor” had not acted on gun violence.

The structure of these speeches are highly intentional. And all these contrasts with Mr. Trump came before Mr. Biden’s recitation of his own accomplishments, or before he discussed any new proposals for the rest of this year or for a second term.

Later — in a moment not in his prepared remarks — he spoke directly to Mr. Trump. “If my predecessor is watching,” Mr. Biden said, before urging the former president to join him in backing the failed bipartisan border bill that Mr. Trump helped tank.

Moments of Mr. Biden’s address were reminiscent of the one he gave a year ago, when he responded to heckles from Republican lawmakers with quick retorts that earned him high marks for being quick on his feet.

On Thursday, he did it again, sparring with Republicans about tax cuts and immigration and more. Once, Representative Marjorie Taylor Greene, Republican of Georgia, yelled during the speech that Mr. Biden’s son should pay his taxes.

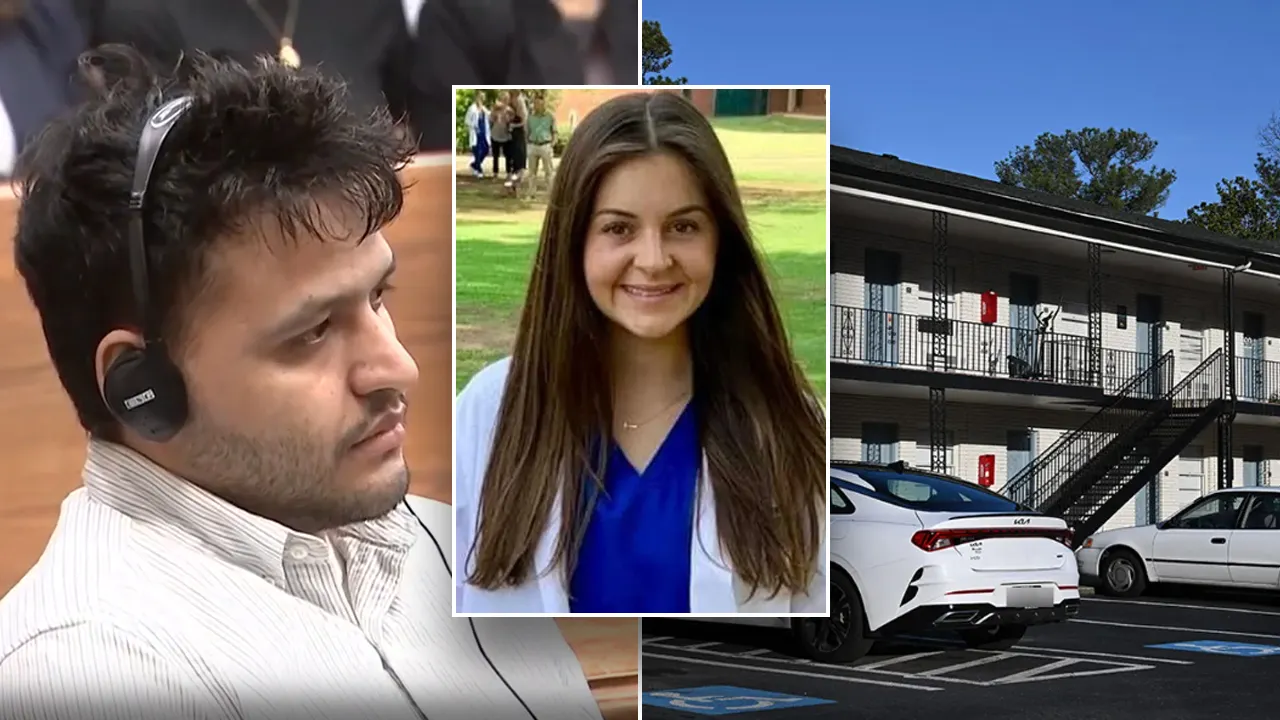

At one point, Mr. Biden held up a pin that Ms. Greene had been handing out ahead of the speech calling on him to say the name of the nurse in Georgia who had been killed. A Venezuelan migrant has been charged with her murder.

Mr. Biden held up the pin and declared, “An innocent young woman who was killed by an illegal,” a term many Democrats have retired.

Mr. Biden and his advisers had prepared — in fact, had been eager for — an interplay with G.O.P. lawmakers. They are betting that people are looking for a fighter and someone who still has the energy to engage with his rivals, politically and on the global stage.

Doing that can be tricky. In some of his news conferences, he has come across as more angry than assertive. In other moments, he has seemed too soft-spoken or weak, prompting some of his supporters to wish that he put more energy into being more assertive.

On Thursday night, with the help of the Republicans, he avoided both extremes. He ended the 68-minute speech with an even louder finish that drew the usual standing ovation from Democrats.

Abortion became an even bigger focus for Biden.

This State of the Union speech was Mr. Biden’s second since Roe v. Wade was overturned. But he devoted far more time to abortion than the 72 words he spent on the subject in 2023. In fact, his prediction that the “power of women” would show itself in 2024 because of abortion was the first excerpt the White House had released before the speech.

On Thursday, he spoke of Democratic victories in 2022 and 2023 since the Supreme Court overturned Roe and he made a prediction.

“We’ll win again in 2024,” he said, because of abortion. It was an explicit political call to arms in the halls of government. The speech itself doubled as a map to the top issues Mr. Biden is running on, including democracy.

“My God, what freedoms will you take away next?” Mr. Biden said.

The centrality of “reproductive freedom,” as Mr. Biden often phrases it, was not just clear from his speech but the guests in the White House’s box. They included a Texas woman who had to leave her state to get an abortion to save her own life and an Alabama woman who had been scheduled for fertility treatments when the Alabama Supreme Court shut down I.V.F. treatments in that state.

The reality, for now, is that the Democratic agenda is more defensive of potential Republican action on abortion. There is little the president can do for abortion rights, which is why his promise to “restore” Roe v. Wade was so carefully crafted to include the hedge that he would do so “if” voters also elect a Congress that could pass such legislation.