Ryan Leaf needed an ally.

The No. 2 pick in the 1998 NFL Draft was coming off a disastrous rookie season for the San Diego Chargers. Two touchdowns to 15 interceptions in 10 games. Eight fumbles and 22 sacks.

The young quarterback completed 45.3 percent of his passes and was benched multiple times. He alienated teammates and verbally accosted a reporter in the locker room. He recently described himself as acting “poorly … as a professional.”

The Chargers fired head coach Kevin Gilbride in October and finished the season 5-11. Leaf characterized the “mentality” of most in the organization at that time as, “If (Leaf) gets hit by a car on the way to work today, we’d be OK.”

That offseason, he was desperate for someone who viewed him differently, who focused on his potential and not his transgressions.

That someone became Jim Harbaugh.

“Everybody else was just like, ‘Screw this kid. I don’t want anything to do with him,’” Leaf recently told The Athletic. “(Harbaugh) wasn’t that guy, ever. He was always there to try to help.”

In two seasons playing quarterback for the Chargers, Harbaugh went 6-11 as a starter, throwing more interceptions than touchdowns. San Diego went 1-15 in 2000. Harbaugh’s final NFL pass attempt came in a Week 11 loss to the Miami Dolphins at Qualcomm Stadium.

Up until three weeks ago, this two-year stretch of Harbaugh’s legendary football life was a relative afterthought. But after Harbaugh was introduced as Los Angeles Chargers head coach on Feb. 1 at SoFi Stadium, this unceremonious end to a 14-year playing career now has revitalized meaning.

GO DEEPER

Home Depot, ‘Ted Lasso’ and an RV: What we learned at Jim Harbaugh’s Chargers introduction

To start the news conference, the Chargers played a hype video on two screens sandwiching each side of the podium. Included were several highlights of Harbaugh in a Chargers uniform. He sat in the front row, the giddy emotion evident on his face, smiling from ear to ear as reflections of the highlights danced on his glasses.

“All of these old memories are flooding back,” Harbaugh said after taking the stage moments later.

His connection to the team, the lighting bolt logo, Southern California, the Spanos family — it all stemmed from these two seasons. In the record books, the stint exists as a 9-24 record. But in the stories from the people who lived it, those two years were so much more — the burgeoning saplings of Harbaugh’s coaching style, raucous golf cart races at training camp, passion-fueled fights with teammates and an unwavering authenticity that resonates with teammates and coaches to this day.

“He beats to his own drum,” said former Chargers running back Terrell Fletcher, “and he likes the music he plays.”

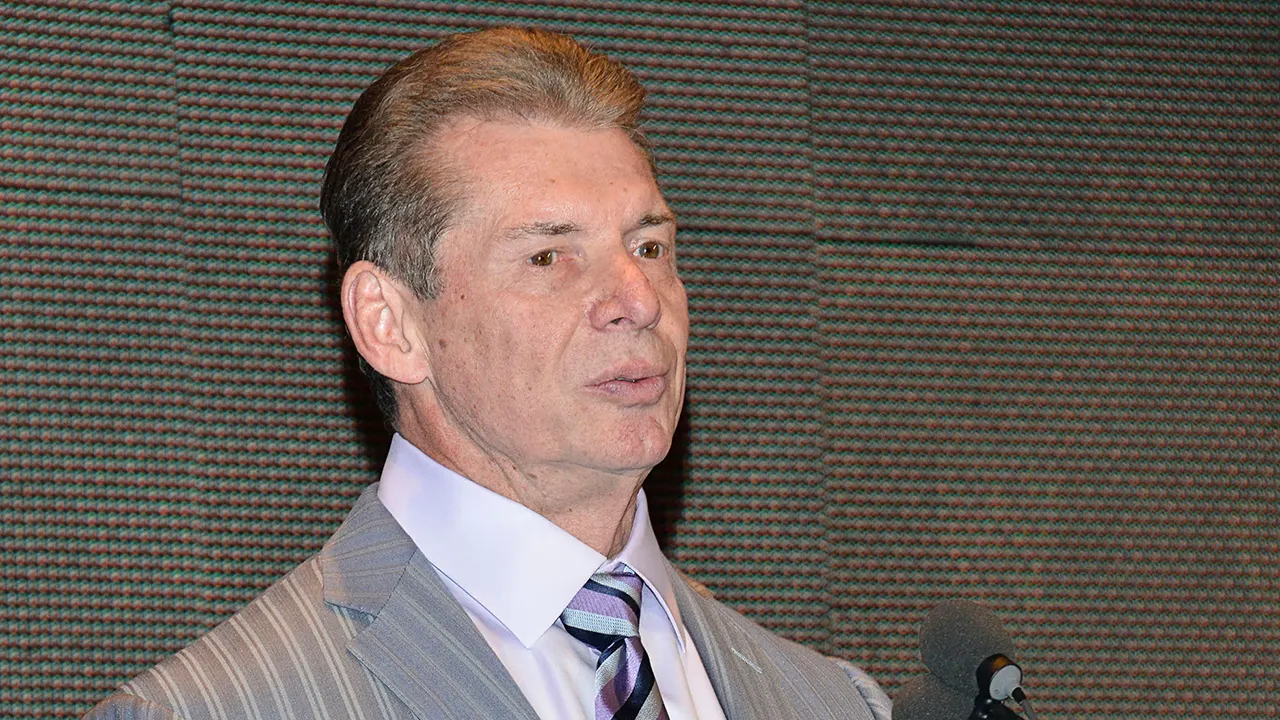

Jim Harbaugh’s two seasons with the Chargers were a relative footnote to a solid NFL playing career until he was hired as their new head coach. (Keith Birmingham / MediaNews Group / Pasadena Star-News via Getty Images)

The Chargers hired Mike Riley as their new head coach after the 1998 season. Riley knew he needed a veteran presence in the quarterbacks room both as an aid and a contingency plan for Leaf. So on March 22, 1999, the Chargers traded a fifth-round pick to the Baltimore Ravens for Harbaugh, then 35 years old.

“What a great choice that was,” Riley said.

Harbaugh was a first-round pick of the Chicago Bears in 1987. In 1995, “Captain Comeback” led the Indianapolis Colts to the AFC Championship Game, beating the Chargers on his way there and making the Pro Bowl after the season. He had thrown for more than 22,000 yards by the time he joined San Diego

Riley was sitting in his office at the Chargers facility one offseason day when he glanced out the window to see rookies on the field going through a workout with the strength and conditioning staff, including lifting and carrying logs.

“You know how the weight coaches are,” Riley said with a chuckle.

As Riley looked onto the field, one player caught his eye, a lone veteran in the group of newbies.

“That’s just Jim,” Riley said. “Jim wasn’t normal.”

This is what Harbaugh brought to the Chargers when he arrived in San Diego in the spring of 1999: “He had an awareness of who he was on a team and what that would mean to the others,” Riley said.

The plan was for Harbaugh to back up Leaf. The previous year, the only other quarterback on the roster had been Craig Whelihan, a 27-year-old who was a sixth-round pick in 1995 and had seven career starts — all losses — to his name.

“We wanted to get a guy that would be not only a mentor type but would be a viable guy if something happened,” Riley said.

Minutes into the opening practice of training camp, Leaf tore the labrum in his throwing shoulder. The contingency became reality. Harbaugh was the Chargers’ starting quarterback.

He debuted for the Chargers on Sept. 19, 1999 — in Week 2, the team had a bye on opening weekend — throwing for 159 yards and two touchdowns in a 34-7 win over the Cincinnati Bengals. He suffered an elbow injury in the first quarter of the third game of the season against the Kansas City Chiefs. Veteran Erik Kramer, signed on the eve of training camp after being cut by the Bears, replaced Harbaugh and helped the Chargers overcome a 14-point deficit to win 21-14.

Kramer started the next two games, wins over the Detroit Lions and Seattle Seahawks (despite four interceptions from Kramer), while Harbaugh nursed the elbow and two cracked ribs. The Chargers were 4-1, with a defense led by linebacker Junior Seau and safety Rodney Harrison emerging as one of the better units in the league.

“We didn’t have a good defense,” said Fletcher. “We had a great defense.”

Harbaugh suited up against the Green Bay Packers in Week 7, but Kramer got a third consecutive start. He threw three interceptions in three quarters and was benched in favor of Harbaugh, who threw three picks of his own in the fourth. The Chargers lost, 31-3.

On the fourth play of a 34-0 loss to the Chiefs the following week, Kramer threw his 10th interception of the season. He fumbled on the next offensive series, the final snap of his NFL career. Harbaugh entered and went on to start the last nine games of the season. Kramer was forced to medically retire midseason because of a neck injury. He recalled waking up in the middle of the night unable to move in the days after the Kansas City game.

After replacing an injured Erik Kramer during a 34-0 loss to the Chiefs, Jim Harbaugh started the final nine games of the 1999 season. (Dave Kaup / AFP via Getty Images)

The Chargers lost six straight games to fall to 4-7. After Week 2, San Diego failed to score more than 21 points in nine straight games. Frustrations mounted among members of a defense that would finish the 1999 season allowing the fewest yards per play in the league.

“We were a little overmatched offensively,” Kramer said. “We didn’t have quite the talent.”

Tensions boiled over in Week 10 during a 28-9 loss at the Oakland Raiders, the fifth of six consecutive defeats. And Harbaugh was at the center of the flare-up.

The Chargers punted on all five of their first-half possessions to open the game, and safety Mike Dumas was waiting on the sideline to greet the offense after each failed drive.

“At first it was kind of encouraging. ‘Come on, offense. Let’s get it going,’” offensive tackle Vaughn Parker said. “But at a certain point in time, you’ve heard it, and it’s like, ‘We get it. We know we’re struggling. Give us a break.’”

The Chargers trailed 21-3 in the fourth quarter when Harbaugh threw an incompletion on a fourth-and-10.

“Mike said something,” Riley recalled. “Jim took offense to it.”

Dumas and Harbaugh got into a jawing match on the sideline. Television cameras picked up the spat.

“It’s really embarrassing us as a team,” Seau said at the time. “We don’t like to see any of our players and family members having a conversation like that in front of millions of people. It doesn’t need to be like that. We don’t need to expose our dirty laundry out there on the street.”

Offensive players, though, saw Harbaugh going to bat for them.

“You appreciate that, especially as an offensive line,” Parker said. “You still wanted to give a great effort for someone who was in it like you were.”

The Chargers lost, 28-9. Riley said he was jogging 20 yards behind Harbaugh and Dumas, who were continuing to yell at each other as they made their way across the field from the visitor’s bench to the Oakland Coliseum locker rooms after the game.

“They held themselves off until they got underneath the stadium and the seats before they actually went at it,” Riley said.

Fletcher pointed out that the fracas was a “football fight, not a real right.” But, he concedes, it is not often the starting quarterback is grabbing facemasks or throwing uppercuts. “That’s one thing that makes it unique,” Fletcher said, “he stuck up for himself.”

“Jim was not going to back down to anything,” Riley said. “That’s kind of his M.O. He’s ready for the fight, whatever it is.”

Harbaugh threw for 677 yards over the next two games. Three weeks after the Oakland loss, the Chargers ended their skid with a 23-10 win over the Cleveland Browns, with Harbaugh completing a season-high 69.6 percent of his passes.

“He is a mad-man competitor,” Parker said.

The Chargers won four of their final five games. The only loss came in Week 15 to the Dolphins. On the final drive, Harbaugh completed six passes to move the offense into field goal range. Kicker John Carney missed from 36 yards. San Diego lost 12-9, finishing one game back of Miami for the final wild-card spot.

The Chargers held training camp at UC San Diego during the years Harbaugh played for the team, complete with players sleeping in dorms and two-a-day practices. “Pads both times,” Fletcher said.

The field was far enough away from the dorms that the team gave players golf carts to shuttle there and back. “They were gas carts,” Parker said. “You could pop the regulator (off) and just make it so much more fast than they anticipated.” Parker remembers a “huge straightaway” on the drive from the dorms to the field.

Compulsively competitive people? Uncapped golf carts? Huge straightaway? Exhausted players craving a reprieve from the dog days of camp?

“We raced the golf carts,” Fletcher confirmed. And who was the ringleader? Fletcher pauses for a second when asked. “It might have been Jim,” he says with a laugh.

Harbaugh, months away from his 37th birthday, was pushing the carts to the limit.

“We had all kinds of things — wrecks and guys falling off,” Fletcher said. “You’d have four people in the cart, two people on the back, the cart’s scratching the ground almost because it’s almost a ton of weight on the carts.”

“Everyone was just ripping,” Parker said.

When teammates think back to 2000, these are the front-of-mind moments. Harbaugh’s levity was among the few positives in a horrific season when the Chargers did not win a game until after Thanksgiving.

Leaf had rehabbed from shoulder surgery and entered training camp in a competition with Harbaugh for the starting job. He completed his first nine pass attempts in a preseason win over the Atlanta Falcons on Aug. 18, finishing the first half with 167 yards and a touchdown.

Not long after, he claimed the starting job. And after the decision was made, Leaf said, Harbaugh was “accepting” and “just nurturing.”

“He all of a sudden became the mentor,” Leaf said. “He became the coach in that quarterback room.”

The Chargers lost the first two games of the season by four combined points, but Leaf threw five picks and lost a fumble and was benched for a Week 3 game against the Chiefs in favor of Moses Moreno. Moreno suffered a throwing-shoulder injury in the third quarter of an eventual 42-10 loss to the Chiefs.

Harbaugh saw his first action of the season the next game against Seattle after Leaf fumbled and threw an interception in the first half. Harbaugh started the next five games, but Leaf got the nod for the final six, including a Week 13 win over the Chiefs, the Chargers’ lone victory of the season.

“It challenged everything (Harbaugh) believes in,” then-quarterbacks coach Mike Johnson said of the 2000 season. “It challenged the way he believes in how you should handle coaches, how you should handle players, everything. Jim Harbaugh has probably never gone 1-15 in anything.”

“A year that’s etched in my memory,” Parker said.

Amid the losing, though, Harbaugh was still making the type of connections that would come to define him as a coach.

Despite the on-field struggles, Jim Harbaugh was planting the seeds of what would make him a successful NFL and college head coach. (Stephen Dunn / Getty Images)

Leaf looked forward to Tuesdays. On the players’ off day, Leaf, Harbaugh and Moreno would play a round of golf. Each week, one quarterback rotated picking the course. Part of the selection process was identifying a course that fit one’s golf game. But Harbaugh was working on a deeper level.

“He always found a really interesting way to corroborate the golf course with kind of a message,” Leaf said.

One Tuesday, Harbaugh picked the course at Coronado to build a theme around the military.

“Everything he did had a coach feeling to it,” Leaf said. “There was always a bigger message that was being sent in everything he did, from the clothes he’s wearing to the golf course he picked for us to play at so he could share stories along the way.”

Don’t be mistaken, though: Harbaugh was vicious during these rounds. Sure, he was coaching — on these days more about life than football. He was also competing.

“They were brutal,” Leaf said. “He suffered no fools, and there was no quarter given. If it was a two-footer to win the hole, he was making you putt it out.”

Still, Harbaugh, in his way, found a way to connect with a man who had lost his connection to virtually everything else in his football life. Leaf said he invited four members of the Chargers organization to his wedding. One was Harbaugh.

“Those two years … he ended up being my best friend,” Leaf said.

It was an unlikely pairing.

“Ryan Leaf and Jim Harbaugh were oil and water,” Johnson said. “Ryan was something that Jim couldn’t understand. ‘How can you be this talented and not be more like me?’”

Johnson remembers one time in the quarterbacks room in 2000, Harbaugh turned to Leaf and said, “Look, Ryan, you’re a poor excuse of a pro athlete. Do your job and make sure you take care of the things you need to take care of to make sure you’re a pro.”

“That’s who Jim was,” Johnson said. “He was not going to allow you to be anything less than what you were supposed to be.”

Harbaugh was supposed to coach. That much was obvious during his playing days. He sat on the sidelines with the Carolina Panthers in 2001 before retiring and setting out on his next career the following season as the Raiders’ quarterbacks coach.

He won a Pioneer Football League title at the University of San Diego in 2005. Five years later, he led Stanford to its first 11-win season in program history and an Orange Bowl title. He took the San Francisco 49ers to the Super Bowl after the 2012 season, and a nine-year run at the University of Michigan, his alma mater, culminated in a national championship in January.

GO DEEPER

Meek: Jim Harbaugh at Michigan could have ended badly. Instead, he delivered a parade.

“You want to be on Jim’s side,” Riley said. “There’s no doubt about it.”

Passionate, principled, driven and authentically himself — that is the legacy Harbaugh left as a Chargers player.

Now he builds a new one.

(Top illustration: Sean Reilly / The Athletic; photos: Brian Cleary and Tom Hauck / Getty Images)