It was past midnight in Berlin and, in the bowels of the Olympiastadion, one England player after another emerged from the dressing room in stony-faced silence. Some heads were bowed, some hoods were pulled up. There goes Harry Kane. There goes Jude Bellingham. There goes Phil Foden. There goes Declan Rice.

It was a night of long walks for England’s players. First, the miserable trudge to the podium, where the European Championship trophy was adorned in red and yellow ribbons — look if you want, but walk on by. Then down staircases to the dressing room, where tears were shed. Now this: a circuitous route to the exit, where a bus was waiting to whisk them off into the night, their dreams of glory dashed once again in a 2-1 defeat by Spain.

Few of them were willing to chat. One who did was John Stones, who described his emotions as “mental torture”. “You think, ‘Could I have done this? Could I have done that? What if this happened?’,” the Manchester City defender said, reflecting on Mikel Oyarzabal’s late winner. “You can play so many scenarios around in your head.”

But defeat had been coming. There had been moments of euphoria as England stumbled through the knockout stage, but in some ways, it was the least convincing of their four major tournaments under Gareth Southgate. They spent more time teetering on the edge of calamity than glory.

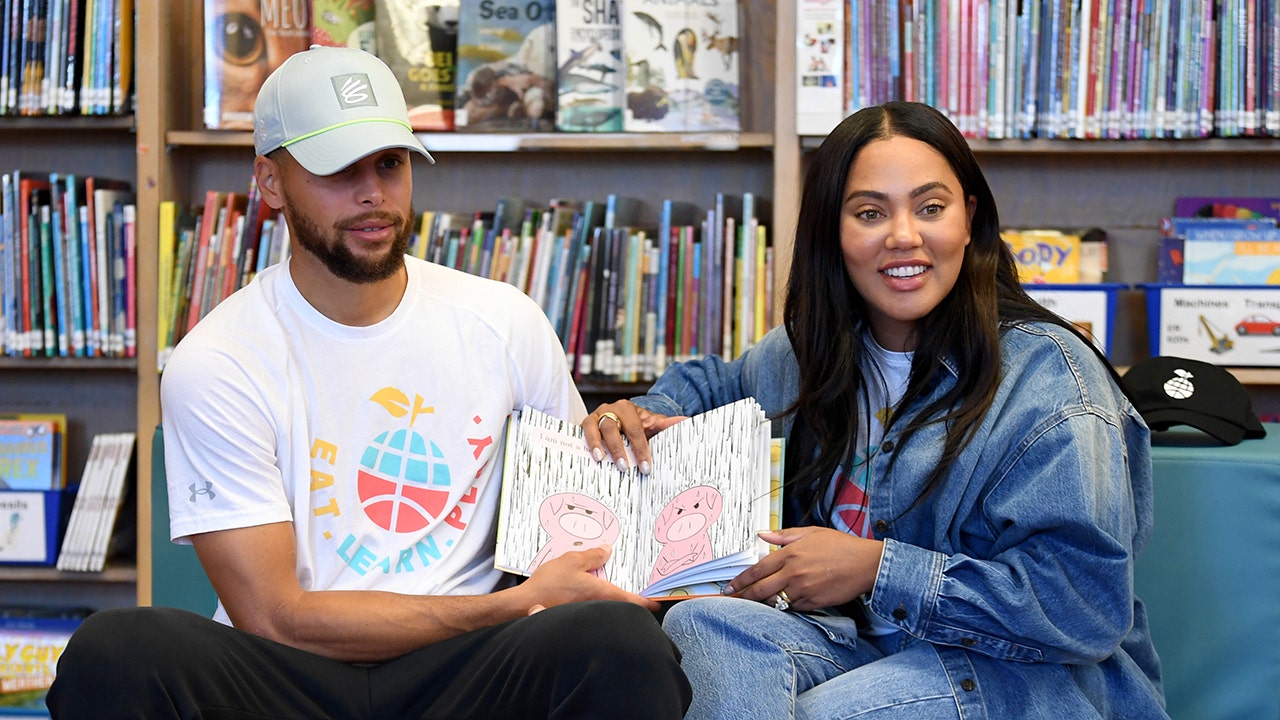

Stones passes the trophy, which now belongs to Spain (Dan Mullan/Getty Images)

It was a strange campaign in so many ways. Southgate repeatedly spoke about the “noise” that was so difficult to overcome, but in the end, there was silence. The only noise was the fiesta coming from Spain’s dressing room down the corridor.

Stones spoke of pride in everything England’s players had done in Germany — “how we handled ourselves, how we gave everyone these memories” — but said that ultimately “it’s just sad”. It felt that way watching them leave, particularly youngsters like Kobbie Mainoo and Cole Palmer, who hadn’t experienced disappointment like this before.

For Southgate, Kane and others, the long lonely walk was achingly familiar.

To tell this story of England’s summer The Athletic has spent the past month speaking to multiple people close to the camp, many of whom have chosen to remain anonymous to protect their relationships.

Five and a half weeks before the final, Kane and Southgate went for another walk. This one was at Tottenham Hotspur’s training ground, where England were gathered before their final pre-tournament warm-up match.

Kane was worried. He and some of his team-mates were in a state of shock after Southgate, having already left Jordan Henderson and Marcus Rashford out of his pre-tournament squad, omitted Harry Maguire and Jack Grealish from the final group of 26.

Southgate had not enjoyed informing youngsters James Trafford, Jarrad Branthwaite, Jarell Quansah and Curtis Jones they had missed the final cut, but they always hoped for inclusion rather than expected it. James Maddison knew the writing was on the wall. Leaving out Maguire and Grealish was going to be much harder.

Maguire knew he faced a race against time, having missed the final weeks of Manchester United’s season with a calf injury. But even after a slight setback, the defender felt he would be fit by England’s third group game. He was shocked when Southgate told him he was out of the final squad. Maguire insisted he would be fit. Southgate told him he couldn’t take the risk.

Grealish was equally stunned. He had made a positive impact from the bench in the friendly against Bosnia & Herzegovina three days earlier and hoped he would be involved in the final warm-up match against Iceland at Wembley, but he too was summoned by Southgate and told he had not made the cut.

Kane and Southgate spoke after a final squad selection that left many players shocked (Richard Pelham/Getty Images)

Maddison left the camp almost immediately. Maguire and Grealish hung around, still shocked. In both cases, that sense of shock was shared by team-mates. Some visited Grealish in his bedroom, expressing disbelief. Rice said in a news conference he was “gutted” that Maddison and Grealish, “two of my best mates in the squad”, had been left out.

Beyond personal feelings, some players simply felt Grealish should have been included because of his quality and big-game experience. He had barely figured in the final weeks of the season at Manchester City, but he started both legs of a Champions League quarter-final against Real Madrid in April. If Pep Guardiola was willing to trust him in big games, why was he suddenly surplus to Southgate’s requirements? Was it personal? Something else?

Grealish wished all his team-mates good luck before he left the camp, but he was in no mood for pleasantries with Southgate. He was shocked and deeply upset. It left a bittersweet feeling among some of the players as they received confirmation of their call-ups. For many, it was not a happy camp that evening.

Grealish and Maddison were both left out of the final squad (Eddie Keogh – The FA/The FA via Getty Images)

Kane was keen to discuss the matter with Southgate so that he could better understand the decision and relay the manager’s thoughts to the rest of the squad. On that walk, Southgate tried to explain his reasoning.

The following evening, England were beaten by Iceland at Wembley in their final warm-up game. There were boos at full time from those who stayed long enough. England had only one shot on target all evening.

For the first time under Southgate, the mood inside and outside the squad felt far from optimal as they set off for a major tournament.

No stone had been left unturned by the FA the staff at their base in Blankenhain in the former East Germany, just over 60 miles from the border with the Czech Republic.

The Spa & GolfResort Weimarer Land had everything from a basketball court, a padel court and a games room, to spa pools, ice baths, relaxation pods and cryotherapy chambers. There were two 18-hole golf courses, to the delight of Kane and others, as well as golf and driving simulators. Each player’s bedroom was decorated with home comforts, family photographs and letters written by loved ones. There was artwork commissioned of various players’ pets, some of them wearing England shirts.

Meals were prepared by Danny Schwabe, the resort’s Michelin-starred chef. It even smelt like home; FA officials had brought diffusers from St George’s Park, their English training base, to make the players feel more at home.

At one time, England players would complain about being shut away in their bedrooms at tournaments. Under Southgate, they spend most of their time in communal areas, whether around the pool (between matches of volleyball and water polo) or around the big screen, watching the other matches, or in the games room or the juice bar. Lewis Dunk and masseur Ben Mortlock set to work on the Lego kits the FA had provided, quickly building the Hogwarts Castle set from Harry Potter.

There was a different dynamic to this squad: no Raheem Sterling, no Henderson, no Sterling, no Maguire, no Rashford, no Grealish.

Some of the personalities within the squad were well established: Kane a quiet leader, Jordan Pickford exuberant, Rice as infectiously enthusiastic off the pitch as on it, Bellingham exuding alpha male energy, Bukayo Saka the universally loved “starboy”. Others would emerge as the tournament went on, not least “Uncle” Marc Guehi, mature beyond his 24 years, and youngsters like Palmer and Mainoo.

Gallagher’s midfield inclusion was curtailed by Southgate (Adam Davy/PA Images via Getty Images)

A favourite pastime was “Werewolf”, from which the TV series “The Traitors” is adapted. Trent Alexander-Arnold and Bellingham, fiercely competitive in everything they do, were the main players — something they referenced with their celebration when Bellingham scored against Serbia to get England’s campaign off to a winning start.

But their performance that day in Gelsenkirchen was unconvincing. England hadn’t hit the ground running the way Germany and Spain had. After a dominant first half-hour, featuring Bellingham’s goal, they had just 44 per cent of the possession and managed just two more shots on target.

There were other concerns. Southgate’s use of Alexander-Arnold in an unfamiliar midfield role had not paid off. The balance wasn’t right. The manager expressed worries afterwards about the physical condition of his players.

Next was a 1-1 draw with Denmark in Frankfurt. Again, there was a lack of fluency and cohesion. Alexander-Arnold was substituted again, this time just 10 minutes into the second half. Southgate seemed to have pulled the plug on that experiment and was now ready to try Conor Gallagher instead.

The team’s energy levels were a real concern now. Southgate spoke of “limitations” in their ability to press because of the “physical profile of the team”. Kane, for his part, said England’s players were “not sure how to put the pressure on and who’s supposed to be going” when the opposition have the ball.

A day later, a report appeared in the London Times detailing the coaching staff’s concerns about the deficiencies in the team’s pressing game, but specifically about Kane. The report detailed conversations Southgate’s coaching staff had previously had with Kane, explaining to him that when pressing an opponent, he has to be at top speed when he reaches them. Kane, the report said, “has never been able to do this. He moves at half-speed towards his opponent, slowing down as he gets there”.

Kane scored against Denmark but was later criticised (Vasile Mihai-Antonio/Getty Images)

The report was by David Walsh, who ghost-wrote a book with Southgate two decades ago and was billed recently as “the journalist who knows him best”. The line about Kane’s pressing might have been historic, or might not have come from Southgate, but it was strikingly specific.

Kane ended the tournament with three goals, sharing the Golden Boot award, but he looked uncomfortable throughout. There were frequent suggestions that he was struggling with the back injury that curtailed his season at Bayern Munich, but publicly, he insisted he was fit.

The issues were piling up, but the biggest of them, according to Southgate, was the one that escalated in the following days.

As much as Southgate was worried about his team’s energy levels, their lack of cohesion, their lack of creative spark and the struggles of Kane, what troubled him most post-Denmark was what he called an “unusual environment”.

This was his fourth tournament as England manager and it was the first time he felt tension in the air. He spoke of “noise” and the difficulty players had in trying to shut it out.

There was still a warmth to media engagements at the team’s base in Blankenhain — built around the now traditional daily player-versus-reporter darts challenge — but some of the players felt they were under attack from former England players including Gary Lineker, who, on his podcast The Rest Is Football, called the performance against Denmark “s***”.

Kane hit back at the pundits, saying they had a “responsibility” to consider the impact of their words on a group of players — some of them at their first tournament — who were already under intense pressure.

At this point, there were whispers from inside the camp about whether Southgate had erred by leaving Henderson, Maguire and others behind. Even if they were not going to get much playing time, some players wondered whether their personalities and experience might have helped bring a sense of calm.

According to those briefed on the matter, one player told a member of Southgate’s staff he had “never known anything like” the criticism the team faced after the Denmark draw, particularly on social media. There had been a backlash after 0-0 draws with Scotland at Euro 2020 and the United States at the World Cup in 2022, but nothing on this scale. Kane was getting stick, but so were Bellingham, Rice, Foden, Kyle Walker, Kieran Trippier and others.

Southgate was troubled by the reaction of his players to the draw with Denmark (Ian MacNicol/Getty Images)

There was also unrest when one newspaper accompanied Walker’s former mistress, the mother of his 10-month-old son, to the game against Denmark. Another player’s marriage was also the subject of media speculation.

The players always look forward to spending time with their families the day after a game, but Kane said some of them felt a seven-hour “fun day”, with bouncy castles and inflatable slides laid on for the children, had been a “bit too long”. “We might cut down on that in future,” he said — and they did.

In the days after the Denmark game, Southgate showed his players some footage from the final whistle in Frankfurt. He openly challenged the players over their body language, telling them, “They (Denmark) are on two points, we’re on four. They’re celebrating with their fans, we’re on our knees.”

Southgate felt their reaction, symptomatic of that “unusual environment”, had fuelled an outside perception of a failing campaign. But the environment got worse before it got better.

First came the boos and jeers. Then, as Southgate made a point of applauding the fans at the end of a dismal 0-0 draw with Slovenia in Cologne, came a stream of insults as the air turned blue. Finally, there were some plastic beer cups thrown in the manager’s direction, which shocked him.

England’s place in the knockout stage was already secure before they kicked a ball against Slovenia, but the mood darkened at the final whistle. It was aimed primarily at Southgate, but the players felt it, too. Ezri Konsa told reporters that some of the players’ family members had been “hit with a few drinks. My brother was hit, a few others. It was coming from all angles”.

So was the criticism. The team just wasn’t working. Bellingham, Saka, Foden and Kane were all struggling. Rice was carrying a heavy load in midfield. There were issues with the balance of the team — the blend in midfield, the lack of width in attack, the absence of a specialist left-back with Luke Shaw still sidelined — but what troubled Southgate above all was what he again referred to as an “unusual environment”.

He reflected after Cologne that the difference in mood was “probably because of me” and that this was now “creating a bit of an issue for the group”.

Empty cups thrown at Gareth Southgate as he applauds the England supporters. @TheAthleticFC #ThreeLions pic.twitter.com/rvJhL6t5OL

— Dan Sheldon (@Dan_Sheldon_) June 25, 2024

There were players Southgate felt he had to take aside. They included Alexander-Arnold, who had been cast aside after two games in midfield, and Gallagher, who was deeply disappointed at being substituted at half-time against Slovenia. Southgate assured both players they would still have important contributions to make, even if they were from the bench. He was pleased by both players’ response over the rest of the tournament.

But Southgate detected an underlying angst within the group. He didn’t go into specifics at the time, but two weeks later, having turned a corner, he was willing to acknowledge it publicly.

“I’ve talked to a lot of psychologists over the years and one of the things that human beings want to avoid is public embarrassment,” he told ITV Sport. “We had a little bit of that mindset in the group stage. We weren’t free. We were too aware of the noise around us.”

One player seemed more aware than anyone. Bellingham’s man-of-the-match performance against Serbia was followed by indifferent displays against Denmark and Slovenia. He was said by those familiar with the team environment to be acutely aware of every word said or written about him in the media. Any criticism of his performances seemed nuanced, but he would later refer to a “pile-on”.

His demeanour was the subject of murmurs. That “Hey Jude” Adidas advert, which portrayed him as the national team’s saviour, was well received by the public, but some within the camp felt the tone was at odds with the collective ethos of Southgate’s England.

Bellingham has followed a different path to his England team-mates: eschewing the Premier League to go from Birmingham City to Borussia Dortmund to Real Madrid. He was fast-tracked through the England development teams without spending much time with others in his age group. Other than a close friendship with Alexander-Arnold, he does not have as many strong connections within the squad as others do.

On the eve of the tournament, Bellingham was promoted to the team’s “leadership group” with Kane, Walker and Rice. But his leadership did not extend to attending any of the daily outside media duties at Blankenhain, whereas less experienced players, including some on the fringes of the squad, such as Palmer, Anthony Gordon and Adam Wharton, faced up and answered awkward questions on the team’s behalf.

This was picked up on by former England captain Wayne Rooney, who wrote in a newspaper column that Bellingham “is in a position where he should be taking responsibility”. “It may be time to grow up, make decisions and say, ‘I need to help out and speak during the difficult times’,” Rooney said, “because if England win these Euros, I’m sure you’ll see him doing interviews.”

Bellingham — and England — needed a big response on the pitch against Slovakia in the round of 16.

England were staring into the abyss. It was the fifth minute of stoppage time and they were on the way out of the tournament, 1-0 down to Slovakia. They hadn’t got a single shot on target. Their campaign — and, it seemed, Southgate’s tenure — was about to end in embarrassment, ignominy and rancour.

And then, after a long throw-in from Walker was headed on by Guehi, Bellingham did something extraordinary, leaping, contorting his body in mid-air and saving England with a spectacular, dramatic scissor kick. Bellingham charged away in celebration. “WHO ELSE?” he asked. “WHO ELSE?”

Well, there was also Kane. In the first minute of extra time, the forward made it 2-1. From facing humiliation in the face, England were heading to the quarter-finals.

This time, Bellingham did the post-match interview rounds, having been named player of the match by UEFA. He said his celebration was partly adrenaline-fuelled but partly a “message to a few people”. “You hear people talk a lot of rubbish,” he said. “It’s nice that when you deliver, you can give them a little back.”

There was also a moment, after that goal, where Bellingham appeared to make a crotch-grabbing gesture. UEFA gave him a suspended one-match ban — to be triggered in the event of a further offence — and fined him €30,000.

Bellingham was the man of the moment, but the biggest pluses for Southgate were the performance of Mainoo, who had brought a better balance to the midfield since replacing Gallagher at half-time against Slovenia, and the contributions of Palmer, Eberechi Eze and Ivan Toney from the bench.

The spectacular Bellingham goal that changed the mood (Shaun Botterill/Getty Images)

There was a different mood as England returned to Blankenhain that evening. Nobody doubted they had got away with a poor performance, but it felt like a weight had been lifted by the euphoria. Back at their hotel, the players bonded, some of them taking Southgate up on his offer of a celebratory beer or two.

The next day brought a recovery session, more family time — a more relaxed mood this time — and, in the evening, a surprise visit by singer Ed Sheeran, who performed an acoustic session for the players, as he had during Euro 2020.

Not every player shares Kane’s enthusiasm for Sheeran’s music, but the night was a great success. Again, the players were allowed to have a drink or two. Some took the opportunity to sing with Sheeran. There was hilarity when Ollie Watkins, an enthusiastic singer, suddenly got stage fright and walked off, telling Sheeran, “Sorry, this song isn’t the one.”

But in a wider sense, the fear of embarrassment had been overcome — just. On the training pitch, on the padel and basketball courts, in those evening games of “Werewolf”, the mood was more upbeat. There was a unity of purpose and a sense of momentum. They were on what looked like the gentler side of the knockout bracket. That helped, too, with Spain, Germany and France all on the other side.

There was also a six-day break between the Slovakia game and the quarter-final against Switzerland: time to recover, recharge batteries and refocus, but also time to work on the training pitch.

Three days before the quarter-final, there were widespread reports that Southgate was considering switching to a three-man central defence against Switzerland. With Guehi suspended after two yellow cards, it was reported that Konsa was likely to join Walker and Stones in central defence, with Saka and Trippier as wing-backs.

Southgate and Holland were livid. Journalists were invited to a conference call where FA officials expressed anger and disapproval on the manager’s behalf. Southgate later asked in an interview with Talksport, “How does it help the team to give the Swiss (who might have been expecting us to play differently) three days to work out what we might do?”

The indignant reaction was a surprise. Media outlets, including The Athletic, have frequently run stories about potential personnel or system changes without attracting such a backlash. The possibility of reverting to a back three, mirroring Switzerland’s system, had already been speculated upon given they had done so in extra time against Slovakia and Southgate had frequently used that system earlier in his tenure.

They worked extensively on the back three in the build-up to the quarter-final. They also prepared for the possibility of a penalty shootout: not just working on their own technique (including the walk-up and the importance of slowing down breathing), but preparing each taker with a designated “buddy” to support him after the kick, to avoid others being disturbed.

The first-half performance against Switzerland was England’s best of the tournament to date, but there was a familiar drop-off after the interval. A sinking feeling took hold even before Breel Embolo gave Switzerland the lead with 15 minutes remaining.

Pickford’s penalty water bottle (Carl Recine/Getty Images)

It was desperation time again for Southgate. Off came Trippier, Mainoo and Konsa. On came Eze, Palmer and, for the first time all tournament, Shaw. Salvation came almost instantly from Saka, the 22-year-old cutting inside from the right and beating Yann Sommer with a shot whipped inside the far post to force extra time. England looked the likelier winners in the first half of extra time, but they ended up clinging on in the closing stages.

Penalties, then: so often the source of English tournament misery in the past, but rarely so (with the Euro 2020 final a notable exception) under Southgate.

Their preparations looked clinical in their precision. So, too, did their penalties as Palmer, Bellingham, Saka and Toney all scored while Pickford pulled off a great save to deny Manuel Akanji (diving to his left, just as the instructions on his water bottle had told him to if the Manchester City defender stepped up).

Alexander-Arnold walked up to take England’s fifth penalty, knowing that he could secure victory. His response was emphatic, a thunderous shot that sent his team through to the semi-finals. On the pitch and in the stands, the celebrations were loud and joyous.

The previous angst had given way to joy and a sudden sense of excitement about what this tournament might now have in store.

There was barely time to rest now. England’s players returned to Blankenhain that night and, after a recovery session the next day, there was only time for two full training sessions before they flew to Dortmund, where they would play the Netherlands in the semi-final on the Wednesday evening.

Southgate reflected on how “at the beginning of the tournament, the expectation weighed quite heavily and of course the external noise was louder than it has ever been”. “We couldn’t quite get ourselves into the right place,” he said. “I felt that shifted once we got into the knockout stages and definitely in the quarter-final.”

The “shift” he spoke about was, he felt, from a “fear mindset” to a “challenge mindset” — being driven by the challenge in front of them rather than consumed by fear of consequences.

But it didn’t quite ring true. They had looked fearful for long periods against both Slovakia and Switzerland, only to be rescued in both matches by a moment of individual brilliance. Performances were still unconvincing. They were going to have to raise their game against the Netherlands.

That need grew after they fell behind to a seventh-minute thunderbolt from Xavi Simons. But they responded well. The manner in which they equalised was fortunate — a Kane penalty following a VAR review which found that Denzel Dumfries had followed through on the England captain — but they were playing more fluently, with Foden enjoying his best 45 minutes of the tournament.

But again they lost their way after half-time. Again they went most of the second half without producing so much as a shot. Foden’s influence had faded after an excellent first half. Kane looked exhausted.

Throughout his tenure, Southgate’s use of substitutions in big matches has been arguably the biggest blot against his record. This time, needing fresh legs, he sent on Palmer and Watkins for Foden and Kane. A big call. Two big calls.

Watkins had only had one brief cameo in the tournament to that point, but earlier in the day, Watkins had told Palmer the pair of them were going to combine for the winning goal. Palmer, receiving the ball in the inside-right channel, knew where to play the pass. Watkins knew where to run. He took one touch to tee himself up and then surprised Bart Verbruggen with a crisp finish inside the far post. England were through to the final.

Watkins creates another euphoric moment (Adrian Dennis/AFP via Getty Images)

The scenes that followed will live long in the memory: Watkins being mobbed by the whole squad, led by Kane; Rice close to tears; Jordan Pickford going berserk; every player looking euphoric, including those who hadn’t kicked a ball in the tournament; Southgate dancing along to “Freed from Desire” and punching the air with delight.

“One more!” Southgate shouted, holding his finger up to the supporters. “Come on!” One more game. One more victory to “make history”, as Southgate put it later.

Spool forward to 10.53pm local time on Sunday. The final whistle was blown and, as Spain’s players and supporters celebrated a deserved triumph, their English counterparts sank into despair.

Rice on his knees. Stones on his back. Saka down, disconsolate. Bellingham walked off the pitch, towards the dugout, and then took out his frustration on a crate of water bottles.

The first half went reasonably well for England. They had far less possession than in previous matches, but Spain’s attacking threat had been kept at arm’s length. Foden forced Unai Simon into an awkward save just before the interval.

But barely a minute into the second half, Spain struck through Nico Williams after the precociously talented teenager Lamine Yamal had escaped from Shaw on the opposite flank. It was a terrible time to concede.

Spain turned the screw, with Williams and Lamal enjoying themselves, and Pickford was repeatedly called into action. Kane gestured to his team-mates to keep going, but it was easier said than done. Again, he looked done for.

Southgate rang the changes, sending on Watkins for Kane and then Palmer for Mainoo. If England were going down, they at least had a duty to go down swinging.

Palmer is the latest to stir England, but this time they did not have the final word (Eddie Keogh – The FA/The FA via Getty Images)

Palmer’s impact, again, was almost immediate. He had barely been on the pitch for two minutes when he struck a first-time shot that beat Simon with the help of a slight deflection. England were back in the game.

It briefly looked like both teams were gearing up for extra time, but Spain found renewed impetus. Yamal forced Pickford into another save and then, in the 86th minute, Oyarzabal played the ball wide to Marc Cucurella and made a perfectly timed run for the return pass, sliding in ahead of Guehi to make it 2-1.

England rallied again, with Rice and Guehi both going close from a corner, but Spain would not be denied.

There was post-match talk of fine margins, as there often is, but this time it didn’t feel that way. England were lucky to end up on the right side of those fine margins earlier in the tournament. They had sailed close to the wind for weeks. It was no surprise when, finally, coming up against a far more coherent team, they were blown off course.

Additional contributor: Dan Sheldon

(Top photo: Getty Images: design: Eamonn Dalton)