LOUISVILLE, Ky. — The thing about a life-changing event that takes two minutes to finish: every move, every decision, even every non-decision matters. Except it’s not just the moves, the decisions and the non-decisions made in those two minutes that matter; it’s a lifetime of split-decision choices that combine to create a life and, in one case on a muggy Saturday evening, make history.

To unspool the story of Kentucky Derby winner Mystik Dan’s historic run along the rail and into the record books requires far more than a rewind around the Churchill Downs track. It includes a decision to not bail on a dinner date 30-plus years ago and a hunt for bloodstock information in the basement of a college library years before even that. It necessitates a commitment to a would-have-been retired mare and a father convincing his son to fall in love with horse racing. It requires one jockey to study another rail-riding rider, and a partnership between a collection of people who compete with the big names but intentionally never cared about being one of them.

On the historic 150th running of this race, Mystik Dan delivered a breath-holding finish, beating second-place Sierra Leone and third-place Forever Young in the first three-horse photo finish since 1947. So close was the finish, not even winning jockey Brian Hernandez Jr. was certain what happened, asking an outrider as he eased Mystik Dan if he’d won the Kentucky Derby.

It took an agonizing five minutes for the answer to arrive, the 156,710 spectators on hand going from euphoric as the three horses neared the wire to near-stunned silence as they, like the jockey, awaited the decision.

Finally, Mystik Dan’s name flashed on the big board, the crowd in the stands whooping in joy, the outrider sharing the news with Hernandez. “It took about two minutes, and then finally when they said, ‘Yeah, you’ve just won the Kentucky Derby, I was like, ‘Oh wow, that’s a long two minutes. That was the longest two minutes in sports — from the fastest two minutes to the longest by far.’’

Perhaps the only person not surprised was trainer Ken McPeek. The Kentucky-based trainer practically made like Babe Ruth and called his shot all week. On Friday, when he sat at a press conference to celebrate his Kentucky Oaks winner Thorpedo Anna, it was suggested that perhaps he’d return for another winning presser the next day. “Count on it,’’ he said. When the promise was delivered, McPeek celebrated on the track, holding his daughter Annie’s hand tight.

By combining the winning ride with that of Thorpedo Anna, McPeek became the first trainer since Ben Jones in 1952 to win the Kentucky Oaks-Kentucky Derby double, and Hernandez the first jockey to do so since Calvin Borel in 2009.

It is fitting that Hernandez matched Borel. In the longer view of this race, the one that makes more like “It’s A Wonderful Life” and considers how even the most inconsequential of decisions lead to an epic life, it was Borel that Hernandez cued up on the videos to study. Borel was known around the track as Calvin Bo-Rail for his love and comfort with riding along the rail, a spot plenty of jockeys would prefer to avoid. When Mystik Dan drew post position three, Hernandez and McPeek started talking about how they might be able to turn what plenty envisioned as a disadvantage into an advantage. Hernandez discovered the secret sauce in the recaps of Borel’s rides.

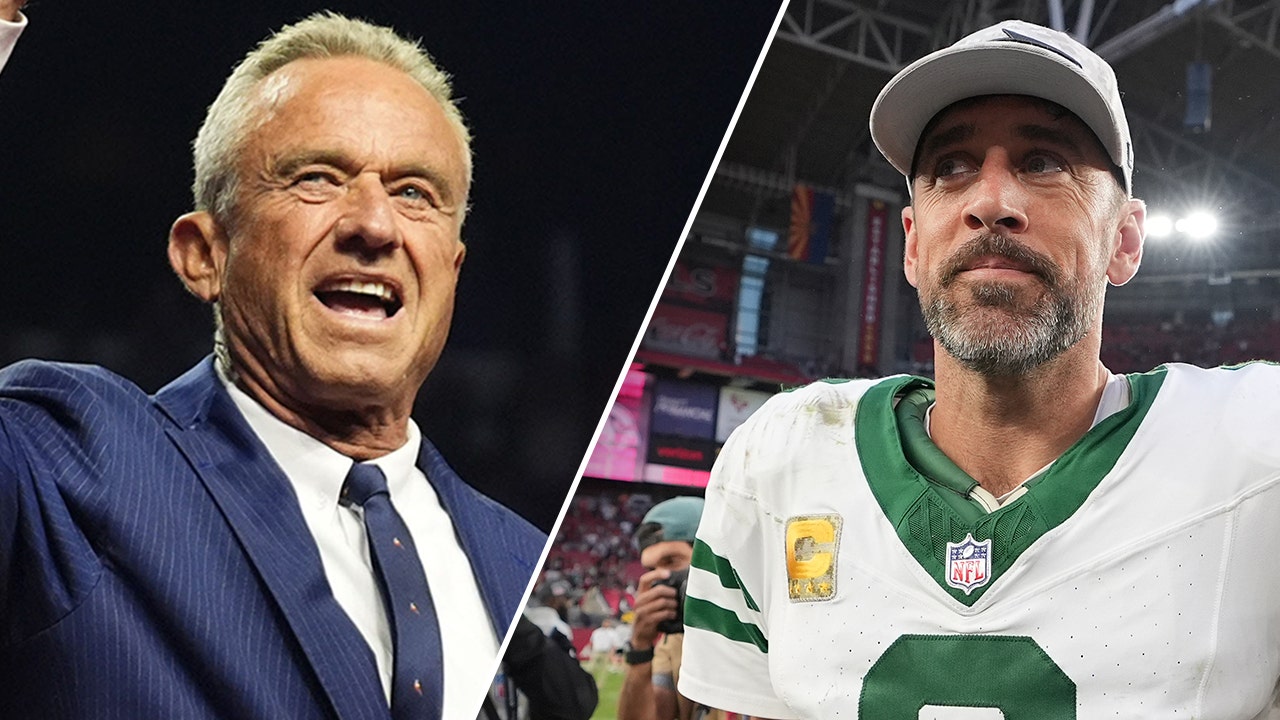

One of Mystik Dan’s owners, Sharilyn Gasaway, holds the 150th Kentucky Derby trophy.

In the immediate here and now, in the 2:03.34 it took Mystik Dan to cover the 1 ¼ miles, the race was won because Hernanedez Jr. steered the horse on a brilliant ride. He followed Track Phantom along the rail, and when the lead horse gave him a half-step’s worth of room, he squeezed Mystik Dan through the narrow space that opened like the sliver of light beneath a doorframe, holding on to the finish line to win by a nose. Favorite Fierceness finished 15th.

But this race was won long before Hernandez cued up the video. It was won some 40 years ago when a young McPeek buried himself in the University of Kentucky agriculture library to educate himself on BloodHorse and thoroughbred records. Taken to Keeneland by his grandfather, McPeek never saw himself doing much else other than horse racing. He jokes that his ag library basement studies might have resulted in better grades than his normal coursework, but it’s only because it fed a passion.

All that studying and poking around, though, created a sort of horse-racing Everyman. He prefers to touch every bit of horse racing and is respected as much as a bloodstock agent as a trainer. He even created an app — Horses Now — for replays. He’s a big believer in the industry, well-liked and well-respected among his peers for his loyalty and decency and his willingness to keep things simple. Horse racing is a big business, and an expensive one, the animals often owned by conglomerates over individuals. McPeek has purposefully tried to eschew that approach. “I think what I’m most proud of is, we didn’t do with Calumet Farm horses,’’ he said, citing the big-breeding conglomerate in Lexington. “We did it with working-class horses.’’

McPeek trained Mystik Dan’s mare, Ma’am, and when she neared retirement, he convinced Lance, Brent and Sharilyn Gasaway not to retire her but to breed her with Goldencents, a 2013 Derby entrant. That they agreed goes to the trust the owners put in McPeek, but also back to their own horse-racing roots and their little moments that led them to a small-ish racehorse with the biggest of wins.

Lance Gasaway, you might argue, is the Mystik Dan of college football. That is to say, perhaps a tad overlooked. A record holder and Hall of Famer, he starred not at Arkansas but at Arkansas-Monticello, where he was an NAIA All-American for the Boll Weevils. He got into horse racing at the urging of his dad, Clint, the two partnering at Oaklawn, their home track. Their biggest and best shot at the limelight came with Wells Bayou, who won the Louisiana Derby and was targeted for the Kentucky Derby until COVID struck and moved the race to September.

Clint died about a year ago, and as Lance sat on the dais, he got more than a little choked up when he recalled his father’s influence. “To me, this is for him,’’ he said. “Dad would have loved it. He loved the game.’’ But a few years ago, back when Ma’am was about to be retired, Clint decided he was getting too old to get into breeding horses. Lance opted to bring in his first cousin, Brent.

Thirty-five years ago, Brent was meant to meet his now-wife Sharilyn for a date, but he was late. And then later. Turns out he was at the track, still at the races. Sharilyn was less than thrilled — at least until Brent that night popped the question. When Sharilyn quit her full-time job, the couple opted to get into horse racing full-time, about the same time that Clint and Lance got into the game. When Lance needed a new partner for breeding and, eventually, in the ownership of Mystik Dan, Sharilyn and Brent made perfect sense.

Sitting side-by-side, sandwiched between McPeek and Hernandez, Lance and Sharilyn both seemed a bit wide-eyed and happily dazed. Asked how they might celebrate, Lance deadpanned, “I don’t know. I never won the Derby before.’’

Neither had McPeek. But now, with his own Triple Crown — he won the Preakness in 2020 with Swiss Skydiver and the Belmont in 2002 with Sarqva — he at least had an inkling. “I’m going to go back to the barn and hug all the staff and all the family,’’ he said. “And then my house is wide open if anyone wants to come over.’’

Mystik Dan may have won the Derby in two minutes of maneuvering, but it took a million smaller moments to create the masterpiece.

(Photo of jockey Brian J. Hernandez Jr. on Mystik Dan: Rob Carr / Getty Images)