BOSTON — On May 10, on his first shift, Brad Marchand tumbled to the TD Garden ice. It took him time to get up.

Bruins HC Jim Montgomery says Brad Marchand is day-to-day with an upper-body injury after this play where he collided with Panthers’ Sam Bennett in Game 3.

(🎥: @Sportsnet)pic.twitter.com/zLPwMauLxC

— theScore (@theScore) May 11, 2024

Once he did, the woozy Boston Bruins captain nearly toppled over. Without assistance from James van Riemsdyk, Marchand might have fallen again or tumbled through the open door of the Bruins bench.

Marchand, in all likelihood, had suffered a concussion. The Florida Panthers’ Sam Bennett had punched Marchand in the face, unseen by most until two days later via an alternate camera angle.

Yet Marchand took 15 more shifts in Game 3 of the second round of the 2023-24 playoffs before the team’s medical staff pulled the left wing. Doctors ruled Marchand out for Games 4 and 5. After the series, Marchand acknowledged he had not been upfront about his condition.

A blood test, approved earlier this year by the Food and Drug Administration, could have made Marchand’s exit and concussion diagnosis quicker and clearer.

Gray area

According to the NHL’s Concussion Evaluation and Management Protocol, a player shall be removed from the ice and taken to a distraction-free environment for concussion evaluation if, among other things, he has a blank or vacant look or is slow to get up. If the player complains of symptoms such as feeling slowed down or not feeling right, he must undergo evaluation.

These are subjective observations and symptoms. Furthermore, the protocol acknowledges such symptoms are not necessarily unique to concussions.

As for the evaluation, part of the process is for the player to complete the Sport Concussion Assessment Tool — 5th Edition (SCAT5). Components include recalling the date, repeating a five- or 10-word series and reciting the months in reverse order. It is a comprehensive test.

But SCAT5 results are only part of a physician’s toolkit. Traditional diagnosis is a medical professional’s judgment call factoring, among other variables, visible signs of an injury and a player’s symptoms, physical exam and SCAT5 results.

“Number one, those tests really lack sensitivity. They’re not perfect,” said Dr. Mike McCrea, a neuropsychologist and director of the Brain Injury Research program at the Medical College of Wisconsin. “Number two, they’re influenced by a whole host of factors — fatigue, distraction, intensity of the moment — other than concussion. All of that then knocks down or limits the accuracy and sensitivity. We have really terrific protocols in place. An important point to make is we do a better job of assessing, diagnosing and managing concussion than we’ve ever done before. But there’s always this piece of the puzzle where we’re hamstrung in not having some objective biological marker of injury.”

Since 2013, McCrea has served as neuropsychology consultant to the NFL’s Green Bay Packers. McCrea has been responsible for making rapid and accurate concussion assessments. It is not black and white.

Consider what doctors like McCrea must deal with: the frenzy of Lambeau Field’s sidelines, subjective clinical and observational tools, players who are not always honest.

“It’s well known that athletes are often not forthcoming in reporting their symptoms,” McCrea said. “Either they lack awareness of symptoms. Or they have a tendency to overlook a given symptom because they’re caught up in the heat of competition. And certainly, in some instances, athletes are not motivated to report symptoms because they don’t want to be removed from play.”

As a neurologist, Dr. Beth McQuiston saw emergency room patients who had suffered head injuries. To help diagnose whether they had suffered concussions, McQuiston would ask what she acknowledges is a tricky question.

“In the current protocol, you say, ‘Do you remember if you forgot anything?’ It’s ridiculous,” said McQuiston. “It’s extremely difficult for people who have a memory impairment to recognize, ‘Oh yes, I have a memory impairment.’”

McQuiston is now a medical director in the diagnostics division of Abbott, a Chicago-based health care company. On April 1, Abbott announced it had received FDA clearance for its i-STAT TBI cartridge, a blood-based rapid concussion test. Doctors who administer the test would know within 15 minutes whether a player has likely suffered a concussion.

The field of blood testing is growing. On July 29, the FDA approved a blood test from Guardant Health to diagnose colon cancer. A day earlier, a Swedish study published in JAMA concluded that a blood test was effective in diagnosing Alzheimer’s disease.

“This will be an enormous and incredibly valuable tool in what we call aid and diagnosis,” said McCrea. “It’s another tool in our toolbox to give us a more valid and accurate assessment of concussion in athletes, independent of all those factors that can sometimes mimic concussion.”

How it works

A concussion typically occurs when the brain strikes the skull. Upon impact, according to McQuiston, the brain releases ubiquitin C-terminal hydrolase L1 (UCH-L1) and glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) into the bloodstream. These proteins are not usually present in blood under normal conditions.

“Imagine if this cup was cracked,” McQuiston said, holding up a drink during an interview at a Boston coffee shop. “The water would start leaking out. That’s what we’re measuring.”

A player suspected of having a concussion has blood drawn via a syringe. Several drops of blood are entered into a cartridge. The cartridge is inserted into a device that resembles a supermarket scanner. The device determines whether UCH-L1 and GFAP levels are elevated or not. If it’s the former, the player has likely suffered a concussion.

Dr. Niko Mihic, director of the executive health program at Hospital de Madrid, participated in a two-month trial run of the test with Real Madrid, where he is a medical consultant. The test addressed one of Mihic’s complaints: player denial.

“They all lie,” Mihic said with a smile. “Nobody wants to tell you the truth. ‘I’m OK.’ Because they all want to get back in the game. They deny it. I think it’s a big part of the reason it’s being underdiagnosed severely.”

Some concussion symptoms take hours or days to develop following injury. By then, if an NHL player has been given the green light to return to play, his condition may worsen.

A prompt and accurate diagnosis, on the other hand, would kickstart recovery. A player can begin immediate physical and cognitive rest. Once a player is symptom-free, he can progress through the exertion stages outlined by NHL protocol: daily activities, stationary cycling, interval and light resistance training, skating, non-contact practice, controlled body contact in practice.

A quicker diagnosis and recovery could, then, hasten a player’s return to play.

Even a test that returns non-elevated UCH-L1 and GFAP thresholds could point doctors toward other solutions. Former NHL defenseman Adam McQuaid estimated he had three or four concussions during his 512-game career. In 2018-19, his final NHL season, McQuaid complained of headaches and fatigue after taking a hit from Andrew Shaw.

McQuaid thought he had suffered another concussion. Only after multiple medical consultations did McQuaid learn he had injured his neck. The injury ended his career. But it comforted McQuaid to know he had avoided head trauma.

“When it’s diagnosed and treated properly, it can be a relatively quick recovery and no issues,” McQuaid, now the Bruins’ player development coordinator, said of concussions. “So if there could be more clarity, it could be helpful for guys.”

The next step will be to convince the NHL, teams and players of the value of an objective concussion test. According to Abbott, no NHL clubs use the i-STAT TBI cartridge. When asked in an email if the league would consider using a blood-based test like Abbott’s, an NHL spokesperson did not reply.

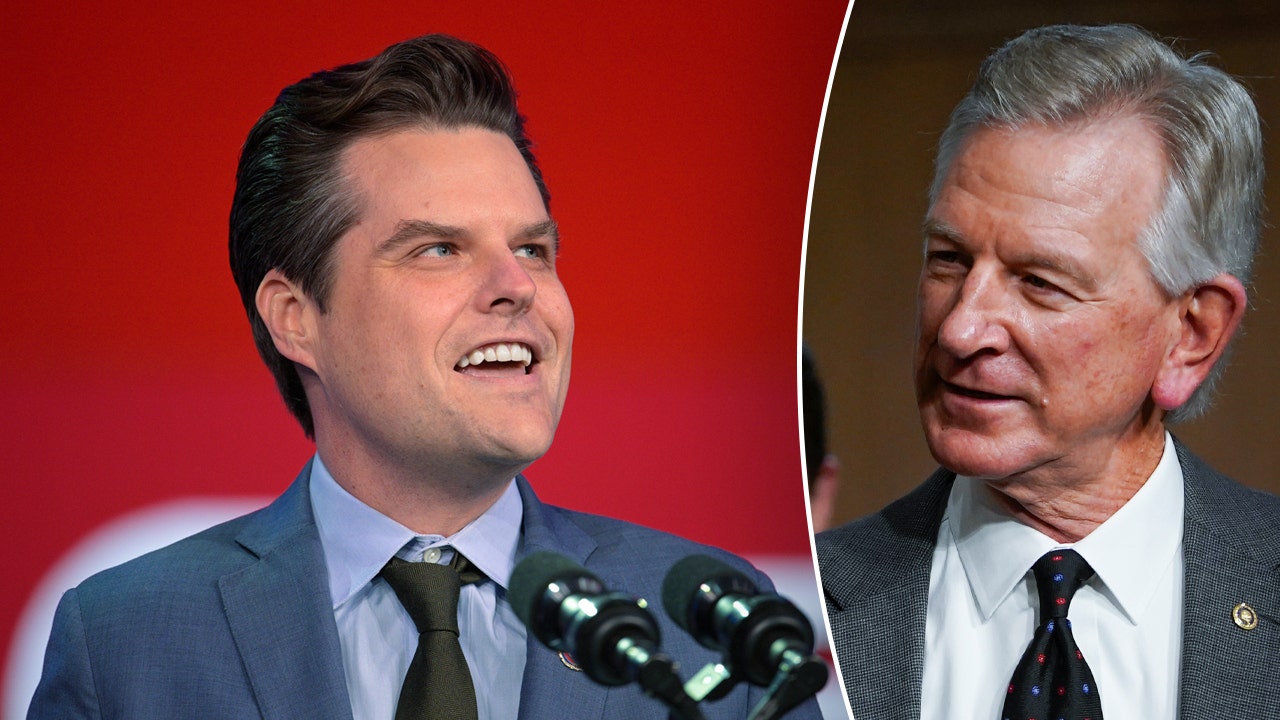

Marchand acknowledged he wasn’t upfront about a concussion he suffered during the second round of the playoffs last season. (Richard T Gagnon / Getty Images)

Culture change

“I need the players to be honest and tell me how they’re feeling,” Colorado Avalanche head athletic trainer Matt Sokolowski said in the NHL’s concussion educational video, which clubs must show annually no later than the first day of training camp. “Do they have a headache? Do they have any dizziness? Are the lights bothering them? Is the sound bothering them? Do they feel nauseous? Any of those symptoms, we need to know and we need to take care of it.”

In May, Marchand’s competitiveness trumped common sense. He would probably have leaguewide company.

Hockey players have a reputation for playing through injuries. They may not be eager to take a test whose result would guarantee removal from play.

Awareness is progressing, though, to where players have a better understanding of concussions’ long-term effects.

“Everyone wants to play this game for a long, long time,” the Bruins’ Charlie McAvoy said in the concussion video. “But aside from that, many of us have aspirations to have long, long, happy lives with families and children and all that. In order to do that, you need to have a full-functioning brain in order to live the life you want.”

Earlier in his career, McCrea interacted with athletes he classified as “aggressively resistant” when told they had likely suffered concussions. They lied about their symptoms. They became angry when informed they had to come out of games.

McCrea does not see that as much now. Players are self-reporting symptoms. They have undergone baseline concussion tests since youth sports.

“What most athletes want, first and foremost, is an informed decision that protects their safety and brain health. That was really not the case 25 or 30 years ago,” McCrea said. “If they have an understanding of how another tool such as blood-based biomarkers could actually improve the diagnosis of concussion — accurately identifying a concussion and accurately ruling it out when it’s not — that’s in their best interest. I think athletes, in the current day, recognize that and will welcome that.”

(Photo of blood being administered into the i-STAT TBI cartridge courtesy Abbott)