Mr. Kristof is the author of a new memoir, “Chasing Hope: A Reporter’s Life,” from which this essay is adapted.

More than three-quarters of Americans say the United States is headed in the wrong direction. This year, for the first time, America dropped out of the top 20 happiest countries in this year’s World Happiness Report. Some couples are choosing not to have children because of climate threats. And this despair permeates not just the United States, but much of the world.

This moment is particularly dispiriting because of the toxic mood. Debates about the horrifying toll of the war in Gaza has made the atmosphere even more poisonous, as the turmoil on college campuses underscores. We are a bitterly divided nation, quick to point fingers and denounce one another, and the recriminations feed the gloom. Instead of a City on a Hill, we feel like a nation in despair — maybe even a planet in despair.

Yet that’s not how I feel at all.

What I’ve learned from four decades of covering misery is hope — both the reasons for hope and the need for hope. I emerge from years on the front lines awed by material and moral progress, for we have the good fortune to be part of what is probably the greatest improvement in life expectancy, nutrition and health that has ever unfolded in one lifetime.

Many genuine threats remain. We could end up in a nuclear war with Russia or China; we might destroy our planet with carbon emissions; the gap between the wealthy and the poor has widened greatly in the United States in recent decades (although global inequality has diminished); we may be sliding toward authoritarianism at home; and 1,000 other things could go wrong.

Yet whenever I hear that America has never been such a mess or so divided, I think not just of the Civil War but of my own childhood: the assassinations of the 1960s, the riots, the murders of civil rights workers, the curses directed at returning Vietnam veterans, the families torn apart at generational seams, the shooting of students at Kent State, the leftists in America and abroad who quoted Mao and turned to violence because they thought society could never evolve.

If we got through that, we can get through this.

My message of hope rubs some Americans the wrong way. They see war, can’t afford to buy a house, struggle to pay back student debt and what’s the point anyway, when we’re boiling the planet? Fair enough: My job is writing columns about all these worries.

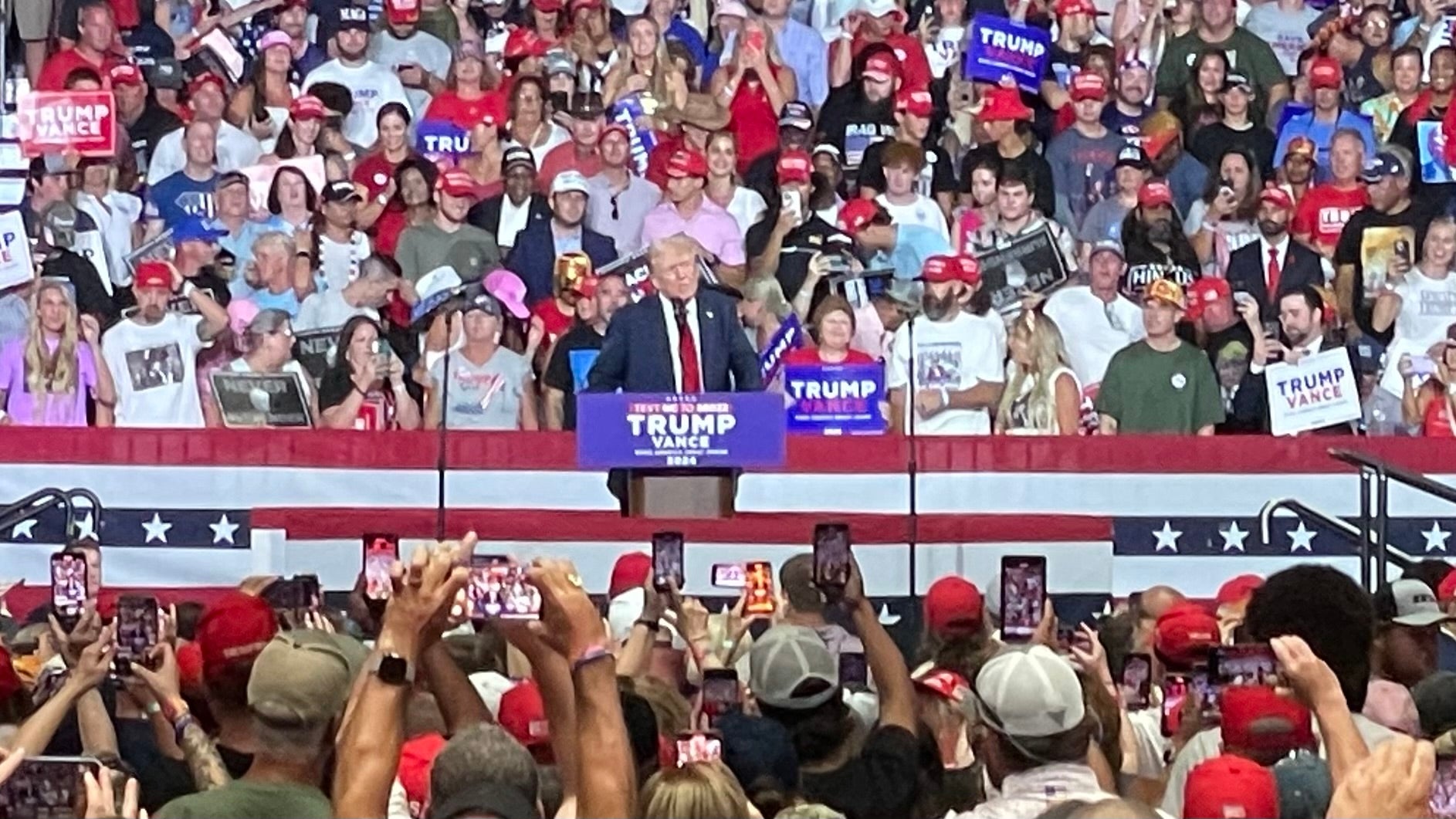

Yet all this malaise is distorting our politics and our personal behaviors, adding to the tensions and divisions in society. Today’s distress can nurture cynicism rather than idealism, can be paralyzing, can shape politics by fostering a Trumpian nostalgia for some grand mythical time in the past.

The danger is that together all of us in society collectively reinforce a melancholy that leaves us worse off. Despair doesn’t solve problems; it creates them. It is numbing and counterproductive, making it more difficult to rouse ourselves to tackle the challenges around us.

The truth is that if you had to pick a time to be alive in the past few hundred thousand years of human history, it would probably be now.

When I step back, what I see over the arc of my career is a backdrop of progress in America and abroad that is rarely acknowledged — and that should give us perspective and inspire us to take on the many challenges that still confront us.

I think of a woman named Delfina, whom I interviewed in 2015 in a village in Angola. She had never seen a doctor or dentist and had lost 10 of her 15 children. Delfina had rotten teeth and lived in constant, excruciating dental pain. She had never heard of family planning, and there was no school in the area, so she and all the other villagers were illiterate.

A young journalist following in my footsteps today may never encounter a person like Delfina — and that’s because of the revolution in health care, education and well-being that we are in the middle of, yet often seem oblivious to.

I have implored President Biden to do more for the children and babies dying in Gaza. I’ve been unwavering about the need to support the people suffering bombardment in Ukraine. And I regularly report on the conflicts and humanitarian disasters in Sudan, Myanmar, Yemen and elsewhere that garner less attention.

Some people see my career covering massacres and oppression and assume that I must be dour and infused with misery, a journalistic Eeyore. Not so! Journalism is an act of hope. Why else would reporters rush toward gunfire, visit Covid wards or wade into riots to interview arsonists? We do all this because we believe that better outcomes are possible if we just get people to understand more clearly what’s going on. So let me try with you.

Just 100 years ago, doctors could do nothing when President Calvin Coolidge’s 16-year-old son developed a blister on a toe while playing tennis on the White House court. It became infected, and without antibiotics the boy was dead within a week. Today the most impoverished child in the United States on Medicaid has access to better health care than the president’s son did a century ago.

Consider that a 2016 poll found that more than 90 percent of Americans think that global poverty stayed the same or got worse over the previous 20 years. This is flat wrong: Arguably the most important trend in the world in our lifetime has been the enormous reduction in global poverty.

About one million fewer children will die this year than in 2016, and 2024 will probably set yet another record for the smallest share of children dying before the age of 5. When I was a child, a majority of adults were illiterate, and it had been that way forever; now we’re close to 90 percent adult literacy. Extreme poverty has plunged to just 8 percent of the world’s population.

Those are statistics, but much of my career has been spent documenting the revolution in human conditions they represent. In the 1990s I saw human traffickers openly sell young girls in Cambodia for their virginity; it felt like 19th-century slavery, except most of these girls were going to be dead of AIDS by their 20s. Trafficking remains a huge problem, but the progress is manifest. In Kolkata, India, where I’ve covered this issue for decades, one study found an 80 percent reduction in the number of children in brothels since 2016.

Two decades ago, AIDS was ravaging poor countries, and it wasn’t clear we would ever control it. Then America under President George W. Bush started a program, Pepfar, that allowed the world to turn the corner on AIDS globally, saving 25 million lives so far. One reason you don’t hear much about AIDS today is that it’s among the great successes in the history of health care.

***

It’s not just that the world has in our lifetimes seen the greatest improvement in human wellness that we know of since the birth of our species. Despite some setbacks for democracy — and real risks here in the United States — I’ve learned to doubt despotism in the long run.

One of my searing experiences as a young journalist was covering that terrible night in June 1989 when Chinese Army troops turned their automatic weapons on unarmed protesters in Tiananmen Square, including the crowd that I was in. You never forget seeing soldiers use weapons of war to massacre unarmed citizens; I still have my notebook from that night, stained with the sweat of fear.

“Maybe we’ll fail today,” my scribbles record, as I quoted an art student nearly incoherent with grief. “Maybe we’ll fail tomorrow. But someday we’ll succeed.”

Yet I also remember a day five weeks earlier in the democracy movement, April 27, 1989, when Beijing students prepared for a protest march from the university district to Tiananmen.

Students knew that if they marched, they were risking expulsion, imprisonment or worse. The evening before, some students spent the night writing their wills in case they were killed.

I drove out to the university district that morning and saw roads lined with tens of thousands of People’s Armed Police. I slipped onto the Beijing University campus by pretending to be a foreign student and watched as a frightened band of 100 students emerged from a dormitory, parading with pro-democracy banners. Gradually other students joined in, and perhaps 1,000 marched, clearly terrified, toward the gate. Rows of armed police blocked their way, but the students jostled and pushed and finally forced their way onto the road. To everyone’s surprise, the police didn’t club the students or shoot them that day. Once the vanguard broke through, thousands more students materialized to join the march.

Word spread rapidly. As the marchers passed other universities, tens of thousands more joined the protest march, and so did ordinary citizens. Old people shouted encouragement from balconies and shopkeepers rushed out to give drinks and snacks to protesters. The police tried many times to block the students, but each time huge throngs of young people forced their way through.

By the time they reached Tiananmen Square, the protesters numbered perhaps half a million. Then they marched triumphantly back to their universities, hailed by the people of Beijing screaming support. That evening at the gate of Beijing University, the students were met not by phalanxes of armed police but by white-haired professors waiting for them, crying happy tears, cheering for them.

“You are heroes,” one professor shouted. “You are sacrificing for all of us. You are braver than we are.”

It was a privilege to witness the heroism of that day. There is much to learn from the commitment to democracy shown that spring by Chinese students.

The exhilaration of that march to Tiananmen Square didn’t last. But in my reporting career, I’ve learned first to be careful of betting on democracy in the short run, and second, to never bet against it in the long run.

Some day, I hope to see the arrival of democracy in China, as well as in Russia, Venezuela and Egypt.

Commentators are always predicting the end of American primacy. First it was the book “Japan as No. 1” in 1979 by Ezra F. Vogel, then Patrick Buchanan’s 2002 right-wing “The Death of the West” and Naomi Wolf’s 2007 leftist “The End of America.” It seemed for a time that Europe might surpass us, while in the longer run China appeared poised to overtake America and become the world’s largest economy.

Yet the United States maintains its vitality. World Bank figures suggest that the United States has actually increased its share of global G.D.P., measured by official exchange rates, by a hair since 1995. Europe today is leaderless and has anemic growth. Japan, China and South Korea are losing population and lagging economically. “Uncle Sam is putting the rest of the world to shame,” The Economist noted recently.

China’s struggles today are particularly important, for it was China that was the foremost challenger to American pre-eminence. Many people around the world thought that China had a more vibrant political and economic model. Yet today China is struggling and even with its population advantage it is no longer clear that China’s economy will ever eclipse America’s. The United States is the undisputed titan in the world today.

As I see it, the possibility of a Donald Trump election hangs as a shadow over America. Yet even if Trump were elected, there is a dynamism and inner strength in America — in technology, culture, medicine, business, education — that I think can survive four years of national misrule, chaos and subversion of democracy. Indeed, Trump might wreck Europe and Asia — by abandoning NATO and Taiwan — even more than he would damage America, in a way that would perversely cement U.S. primacy.

Note that one of the dominant issues in this year’s general election will be immigration. That’s partly because of the determination of people around the world to come to America, just as my dad risked his life to escape Eastern Europe and make his way here in 1952. Desperate foreigners sometimes see our nation’s resilience more clearly than we do.

I have seen that faith in America in surprising places, even when I periodically slipped into Darfur to cover the genocide there in the 2000s. I couldn’t obtain a government pass to get through checkpoints, but I realized that U.N. workers were showing English-language credentials that the soldiers surely couldn’t read. So I put my United Airlines Mileage Plus card on a lanyard, drove up to a checkpoint and showed it — and the soldiers waved me through.

Recklessness caught up with me, and eventually I was stopped at a checkpoint and kept in a detention hut decorated with a grisly mural of a prisoner being impaled by a stake through the stomach. It was a frightening wait as the soldiers summoned their commander. He eventually arrived and ordered me released — and then one of my captors who previously had seemed ready to execute me sidled up.

“Hi,” he said. “Can you get me a visa to America?”

***

I share the view that a Trump election would pose immense damage to American political and legal systems. But in the scientific world we would continue to move forward with new vaccines for breast cancer, new drugs to combat obesity and new CRISPR gene-editing techniques to treat sickle cell and other diseases.

How can we weigh democratic decline against lives saved through medical progress? Of course we can’t. As my intellectual hero, Isaiah Berlin, might say, they are incommensurate yardsticks — but that does not mean that they are irrelevant to our well-being.

And no one can accuse me of ignoring the problems that beset us at home and abroad, for they have been my career. They’ve left me a bit too scarred to be a classic optimist. Hans Rosling, a Swedish development expert, used to say that he wasn’t an optimist but a possibilist. In other words, he saw better outcomes as possible if we worked to achieve them. That makes sense to me, and it means replacing despair with guarded hope.

This isn’t hope as a naïve faith that things will somehow end up OK. No, it is a somewhat battered hope that improvements are possible if we push hard enough.

In 2004 I introduced Times readers to the story of an illiterate woman named Mukhtar Mai, whom I met in the remote village of Meerwala in Pakistan. She had been gang-raped on order of a village council, as punishment for a supposed offense by her brother, and she was then expected to disappear in shame or kill herself. Instead, she prosecuted her attackers, sent them to prison and then used her compensation money to start a school in her village.

Instead of giving in to despair, Mukhtar nursed a hope that education would chip away at the misogyny and abuse of women that had victimized her and so many others. Then she enrolled the children of her rapists in her school.

Mukhtar taught me that we humans are endowed with strength — and hope — that, if we recognize it and flex it, can achieve the impossible.