Around 717 million years ago, Earth’s humid landscapes and roiling blue waters transformed into a frigid, barren world. Scientists nicknamed this stage of geological history, and others like it, Snowball Earth.

What exactly froze the planet nearly solid has been a mystery, as has how it remained that way for 56 million years. On Wednesday, a team of researchers at the University of Sydney said they have it figured out. Earth’s glaciation, they say, may have come from a global drop in carbon dioxide emissions, a result of fewer volcanoes expelling the gas into the atmosphere.

Less carbon dioxide makes it more difficult for Earth’s atmosphere to trap heat. If the depletion were extreme enough, they argued, it could have thrust the planet into its longest ice age yet.

The theory, published in the journal Geology, adds insight to the way geological processes influenced Earth’s past climate. It may also help scientists better understand trends in our current climate.

“These days, of course, humans are having a large impact on CO2 in the atmosphere,” said Adriana Dutkiewicz, a sedimentologist at the University of Sydney who led the study. “But back in time, there were no humans, and so everything was basically modulated by geological processes.”

There are many ideas about what turned Earth into a snowball. One popular theory suggests that minerals released by the weathering of igneous rock sucked enough carbon dioxide from the atmosphere to set off a deep freeze.

Perhaps that helped kick off a global glaciation, Dr. Dutkiewicz said, but it couldn’t have kept Earth frozen for 56 million years on its own.

“So there has to be another mystery mechanism that would have sustained the glaciation for that long,” she said.

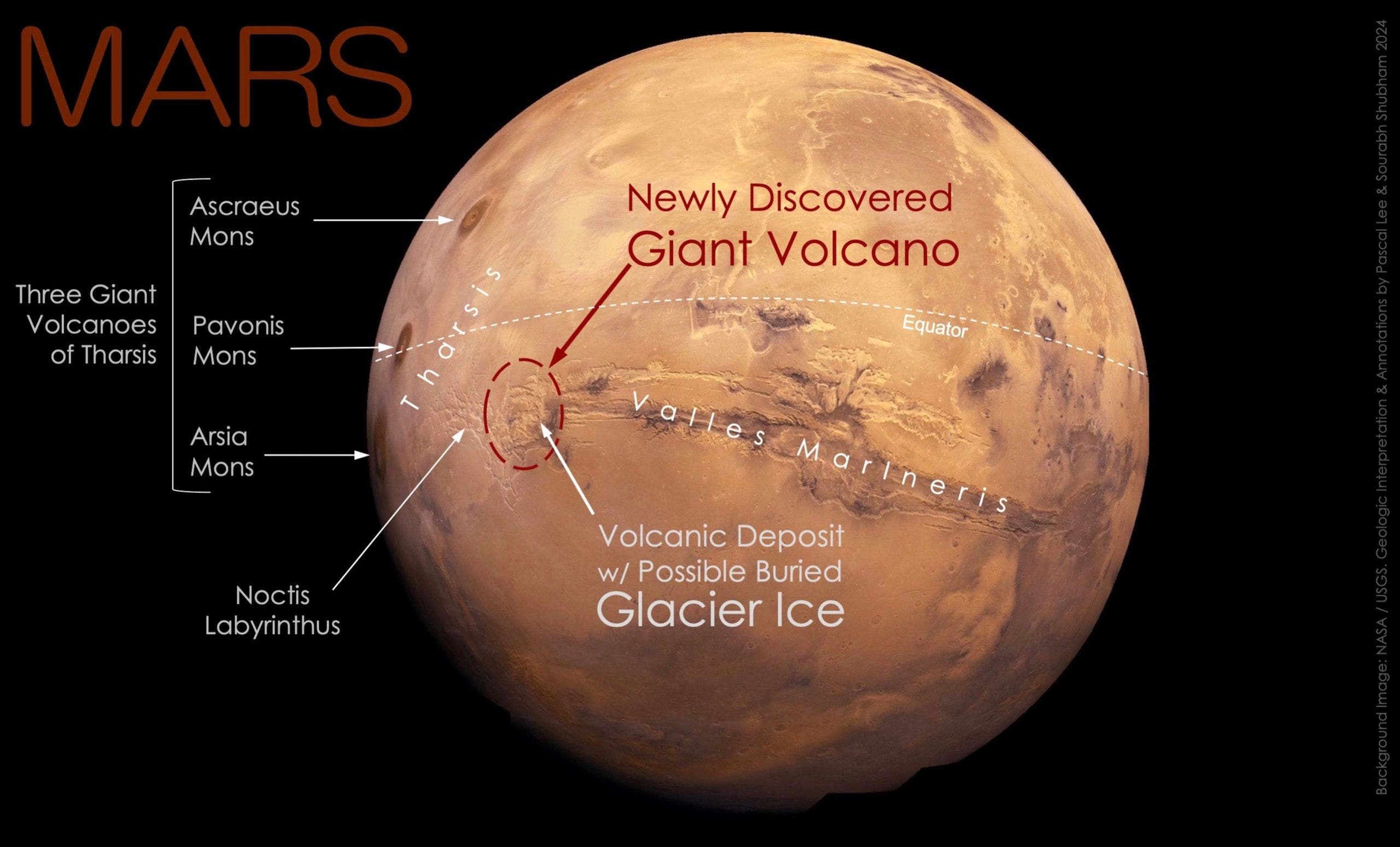

Dr. Dutkiewicz and her colleagues turned their eyes to volcanoes because of a newly available model of Earth’s shifting tectonic plates. As the continents spread apart, they studied the changing length of the mid-ocean ridge — a chain of underwater volcanoes — predicted by the model.

The team then calculated the amount of volcanic gas emissions at the beginning of, and throughout, the ice age. Their results showed a drop in atmospheric carbon dioxide sufficient to initiate and sustain a 56-million-year glaciation.

A reduction in volcanic gas emissions has been proposed as an explanation for Snowball Earth before. But according to Dr. Dutkiewicz, this is the first time researchers have proved that the mechanism was viable through modeled computations.

Dietmar Müller, a geophysicist at the University of Sydney and an author of the study, said the work was one way “to distinguish between alternative models for this very ancient part of Earth’s evolution.” If scientists know there was an ice age, Dr. Müller explained, “then we can say this one reconstruction model is perhaps more likely than the other one.”

Of course, a model is still just that: a model. Without real-world data to back it up, the researchers can’t rule out other possibilities.

“One thing about geology, there are no definite answers,” Dr. Dutkiewicz said. “But based on a combination of different lines of evidence, we can suggest that this is a very likely process.”

Francis Macdonald, a geologist at the University of California, Santa Barbara, who was not involved in the work, said studies like this were important for learning about why climates fail. But he is hesitant to readily accept outcomes from models of the ancient seafloor, because there is little data revealing what Earth’s oceanic crust was like at that time.

“How do we actually test that?” Dr. Macdonald asked about the team’s model. “I think it’s a really big challenge.”

Still, Dr. Müller thinks it is important to try to put bounds on the amount of volcanic gas emitted in the past, particularly when it comes to running climate models for the future. “Usually, that’s the most uncertain parameter,” he said.

Research like this can help scientists distinguish the influence of geological activity from human-induced climate change. But could a natural drop in volcanic emissions ever save us from the amount of carbon we have pumped into our atmosphere today?

“Unfortunately not,” Dr. Dutkiewicz said. “We can study these ancient perturbations,” she added, “but the human-induced change is a different kind of beast.”